Turtle dove

Since visiting Martin Down NNR on a field trip while I was studying for my degree, I have returned countless times during different seasons over the years to marvel at the rich wildlife that this site holds, and it became my favourite place from my very first visited nearly 20 years ago.

For those of you who haven’t had the pleasure of visiting the “Down”, as the locals call it, it is a 350-hectare site of unspoiled chalk downland with scrub, of national importance for its rich archaeology and wealth of downland wildlife. The ancient uncultivated chalky soils support a huge range of rare flowers that have evolved to eke out a living from nutrient-poor soil.

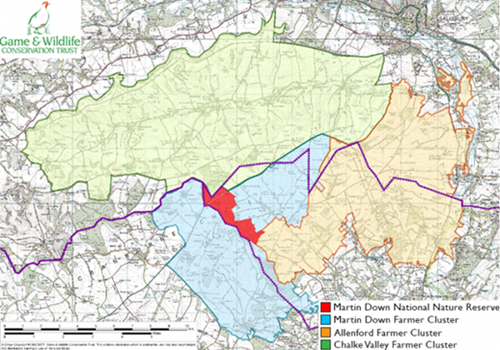

This site is not only important botanically, but also for insects, mammals and birds, especially farmland birds, and is cradled on all sides by the Martin Down Farmer Supercluster. Three Farmer Clusters have joined together, covering 236km2 to protect and enhance the iconic and threatened wildlife of Martin Down. It also aims to establish habitat links across and within the three clusters, reconnect existing wildlife-rich features such as chalk downland, and protect, encourage and monitor the characteristic wildlife species of arable and mixed farmland.

From visiting this site like a pilgrimage over the years, I now have the privilege of working in this landscape every day and with all the farmers, keepers, land managers and landowners in two of the three Farmer Clusters (Allenford and Martin Down) as the Facilitator – what an honour!

Martin Down is one of the most westerly sites of breeding turtle doves (Streptopelia turtur) in the UK, so as you can imagine this was always a reason to visit from late April to September. More recently, this bird has become even more important to me as it is one of the priority species of the Farmer Clusters and will be this month’s Species of the Month.

Turtle dove landing to drink from one of the “turtle dove puddles” created on Martin Down Farmer Cluster

The turtle dove is the UK’s smallest native Dove (L25-28cm, WS 45-50cm) and one of five other species of turtle dove. Our turtle dove is much smaller and darker than a collared dove and slightly larger than a blackbird. Its upperparts are distinctively mottled with chestnut and black, and its black tail has a white edge, like a white laced fan. It has a patch of black and white stripes on the neck and orange eyes – you will know if you have seen one through your binos, they are quite distinctive!

Turtle doves are migratory, the only long-distance migratory dove species in Europe, heading off to Africa in the winter, arriving back in the UK in spring from April – migrating more than 5,000km. They build nests in thick, thorny hedgerows and scrub, such as hawthorn, and will often build nests among climbers, including honeysuckle. They feed in open habitats, most commonly on arable and mixed farmland, where its staple food is wild arable plants seeds and cropped grains which are found on the floor.

The turtle dove’s gentle ‘purr’ is an evocative sound of summer, and a sound that always makes me think summer has finally arrived. Turtle doves have featured in art and culture for thousands of years. Their beauty, song and behaviour inspired Ancient Greeks and Romans, Elizabethan poets, modern musicians, and painters. Perhaps because of their endearing, soothing purr and tender affections when seen perched in pairs, they have long been symbols of love.

However, the story of the turtle dove is unfortunately far from romantic. The UK has around 14,000 breeding pairs of turtle dove according to their last national population estimate in 2009, and are the UK’s fastest declining bird species threatened with global extinction (IUCN Red List of Endangered Species) and has been Red listed in the UK since 1996, and still remains there today. There are four main factors associated with the decline of turtle doves. These include the loss of suitable habitat in both the breeding and non-breeding range, the availability of clean accessible water, unsustainable levels of hunting on migration and disease.

Research points towards the loss of suitable habitat on the UK breeding grounds and the associated food shortages for turtle doves being the most important factor driving turtle dove declines and research carried out in England shows that adult turtle doves are producing half as many chicks as they were in the 1970s. Turtle doves are obligate granivores – their diet is made up exclusively of seeds (such as chickweed, fumitory) and the lack of available weed seeds in the countryside, as well as a dietary switch from weed seeds to cereal grains has been associated with an alarming reduction in nesting attempts.

Resulting in a much shorter breeder season with fewer nesting attempts, this alone is sufficient to explain the current rates of decline. They also fly the gauntlet being shot at on migration and if estimates are accurate, hunting may constitute a significant factor driving population declines as well.

The best chance you have to see the species is in East Anglia and South-east England, where it has maintained its highest densities, but maybe you could help support this species before it is too late, by keeping some weedy open areas on your land, providing some shallow access to water and leaving a few hedges scrubby - before this bird just becomes a memory and a line we sing at Christmas.

Megan Lock

Advisory