It’s clear that poor nest and chick survival has driven the long-term decline of breeding waders in the Avon Valley. Foxes are an important predator of lapwing, redshank and other ground-nesting birds during the breeding season, but they’re difficult to manage, and we know little about their ecology in river valleys and wet grassland dominated habitats.

To effectively mitigate against the impact of foxes on waders, we need a clear understanding of how foxes live, not just in terms of their diet, habitat use and daily patterns of movement, but their population dynamics too. We have lots of questions:

What sort of fox densities are we dealing with? How productive are they? How quickly do foxes infill on sites where they’re culled? How ‘detectable’ are foxes that forage in the best wader breeding habitats, using conventional techniques such as lamping, high-seat counts, and field-sign surveys? Do lethal or non-lethal methods of predation control work best?

To answer some of these questions, as part of the LIFE Waders for Real project with are undertaking studies of Red fox diet, population genetics and movement.

Satellite-tracking devices have revolutionised what we know about the movements of woodcock, especially their migration patterns. Now we’re using similar technology to explore the lives of foxes. As part of the project, our project predator manager has been catching foxes and fitting them with GPS-tracking collars. Foxes are caught between March and May, deploying GPS collars to cover the wader breeding season. In 2016 and 2017, this was on land where waders historically bred, but where habitats were still suitable and in 2018 this moved to one of our wader hotspot sites where lapwing were breeding.

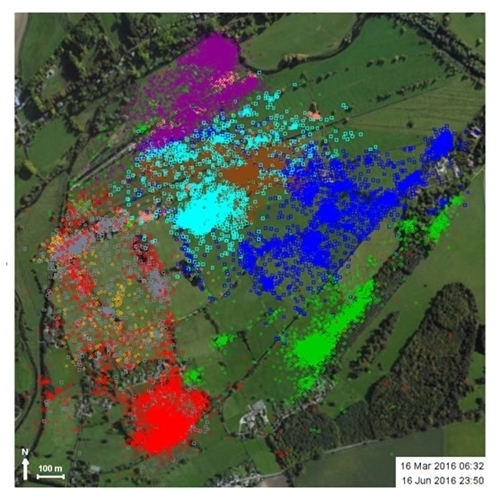

This study is providing fascinating insights on a topic we knew very little about. This work is on-going, and it will be some time before we’ve analysed all the data, but one thing is certain foxes in our study sites are living at a very high density, not far short of what we see in urban environments. Initial results show that foxes are living at very high densities in parts of the Avon Valley. The map below shows coloured dots indicate repeated locations of nine different adult foxes on our study site during March to June 2016. Locations of some individuals are partially masked by the sheer density of overlaid data. In addition, we know there were a similar number of untagged adult foxes occupying the same area through high-seat surveys with thermal equipment and camera-trapping.

As we unravel the lives and daily activity patterns of foxes and figure out the most reliable way of detecting them in this environment, we’ll be much better placed to provide researched-based advice on their effective management in the Avon Valley and elsewhere.