Key findings

- PIT tag technology enabled us to log visits of hares to feeding stations.

- Around half the hares fitted with PIT tags on our study moors took supplementary feed, and the individual use of supplementary feed was variable.

- Feeding had no clear effect on survival, but in April male hares on the fed areas were in better condition, and females appeared to breed earlier.

- Over-winter food availability may play a role in driving mountain hare population dynamics.

In our Review of 2003, we reported on studies that investigated the effects of the gut parasite, Trichostrongylus retortaeformis, on mountain hares. These showed that reducing parasite burdens increased female fecundity (the ability to reproduce), and that this parasite may therefore contribute to instability in hare populations. Food is another possible factor limiting or regulating populations. Supplementary feeding studies, which are widely used to investigate the role of food limitation, assume that supplementary feed is used by the study population and that all individuals have equal access, but this has rarely been tested.

The aims of this project were two-fold. Firstly, to test Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tag technology, (PIT tags are similar to the micro-tags used to identify dogs), and use it to monitor individual hare use of feeding stations. Secondly, through radio-telemetry and repeated live-trapping, to investigate how supplementary feed influenced survival, male body condition, and female fecundity.

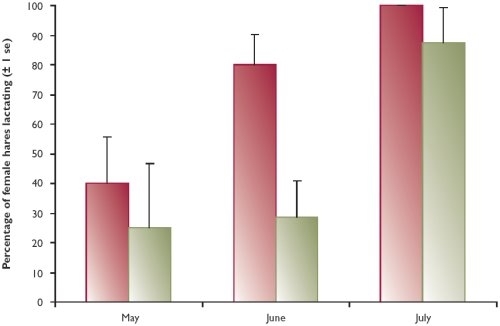

Figure 1: Percentage of female mountain hares with (fed) and without (unfed) access to supplementary food that were lactating in early summer 2006 in Strathspey

In autumn 2005, we deployed custom-made feeding stations on two moors in Strathspey. Each station was equipped with PIT tag sensors, a decoder and data logger that could read and log PIT tags fitted to wild mountain hares while the hares fed from the feeding station. We fitted 125 individual hares from two moors with PIT tags, and over the six-month period of supplementary feeding (October 2005 to April 2006) about 120,000 visits to the feeding stations were logged. In addition an unknown number of non-tagged hares also used the feeders. Intriguingly, of 71 PIT-tagged individuals resident on the two fed areas, only 55% were logged using the feeding stations and there was considerable individual variation in the number and duration of feeding bouts.

The second part of the study examined the survival, body condition and fecundity of hares on fed and unfed areas. Only 26% of the radio-collared individuals survived until the end of the study on the unfed areas compared with 54% on the fed areas, but the difference was not statistically significant. After correcting for body size, males on the fed plots were significantly heavier in April than males on the unfed plots. In April 82% of female hares were pregnant on the fed plots compared with 57% on plots where there was no supplementary feeding, and the proportion of hares lactating during the 2006 breeding season suggested that females on the fed plots bred earlier than did females on the unfed plots (see Figure 1).

Mountain hare populations on heather moorland managed for red grouse sometimes show regular and dramatic changes in numbers and these are often described as cycles. Analysis of mountain hare bag records show that although 50% of the records could be described as cyclic, changes in the length of these cycles (measured from a peak in numbers to the next peak) ranged from four to 15 years. It is currently unclear why some populations are cyclic and others are not, or why there is such a large range in the length of cycles. This study was one of the first to quantify successfully individual use of supplementary feed and, given the limitations of the study, it suggests that over-winter food availability might have a role in affecting changes in mountain hare population size.