Key findings

- 2003 saw the first data collected on the River Monnow.

- Initial juvenile brown trout numbers were moderate.

- Initial adult brown trout numbers were poor.

- There is no measurable change in trout numbers in restored areas.

- Habitat quality has improved in restored areas.

The upper River Monnow catchment suffers from widespread stock access and over-shading. This causes the suppression and destruction of marginal vegetation, which is important as an erosion buffer during winter spates and acts as a form of cover for trout, other fish and aquatic invertebrates. The aim of the project is therefore to restrict stock access by fencing and increase illumination by coppicing.

One of the main reasons for monitoring fish in the River Monnow project is to measure and compare the impact of fencing and coppicing on brown trout on high-and low-gradient rain-fed rivers. This work is important in telling us what type of rivers respond best to the fencing and coppicing treatment, so that we can direct funding more effectively. This comparison is possible because the upper Monnow catchment, the target area for the project, consists of four main tributaries. Three of these, the Olchon, upper Monnow and Escley, are typical high-gradient streams, with fast riffles flowing over a boulder and cobble substrate. The fourth, the Dore, is a low-gradient stream with a typical meandering pool/riffle sequence over a gravel substrate.

Our project has many similarities to our research on the Clywedog Brook, which also suffered from over-grazing and over-shading problems. However, the Clywedog flowed over a ‘moderate’ gradient, which is not typical of all river types. One of the unfortunate aspects of such research is that monitoring must continue over a number of years to be able to measure fully the impact of habitat management techniques. We are hoping, if funding permits, to go back to our experiment on the Clywedog to measure the impact of the fencing and coppicing that was undertaken in 1998 and 1999 as part of the Wye Habitat Improvement Project.

The initial baseline study

In 2003 on the Monnow, we put in place our experimental design, which consisted of 10 pairs of adjacent randomly - selected 500-metre control and management stretches on the four streams. During the summer, we undertook a baseline electro-fishing survey to measure densities of fish before fencing and coppicing began. During the 2003/2004 winter, the management sites were fenced and coppiced.

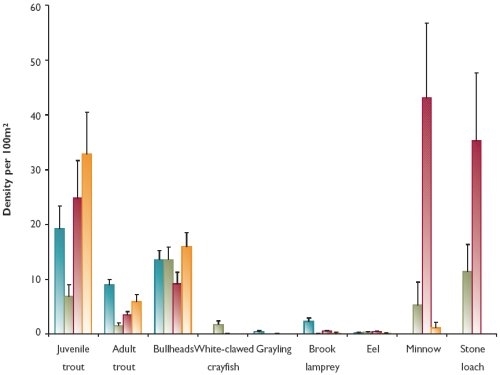

As well as counting and measuring brown trout in the baseline survey, we also gathered data on bullheads, brook lampreys and, in conjunction with Cardiff University, white-clawed crayfish (see Figure 1). Each of these species has an important European conservation status (each is a Biodiversity Action Plan species and is listed in Annex 2 of the EU Habitats Directive). Other fish species caught and recorded included grayling, eel, stone loach and minnow.

Figure 1: Baseline survey of the species in four tributaries of the River Monnow

Early indications from the results of the baseline monitoring suggest that numbers of juvenile brown trout are moderate, but numbers of older trout are generally poor and these data are similar to those recorded on the Clywedog in 1998.

Therefore, there is plenty of room for improvement and, hopefully, when the habitat measures start to take effect over the next few years, the Monnow will once again be regarded as one of the premier wild brown trout fisheries in the country.

Effects of restoration on the trout population

An important part of the project has been to measure trout abundance before and after habitat restoration. This is being done with electro-fishing surveys on 10 pairs of randomised experimental treatment and control sites.

We have also measured the effect of the restoration work on the number of bullheads, which are important as a species listed at risk in the EU Habitats Directive.

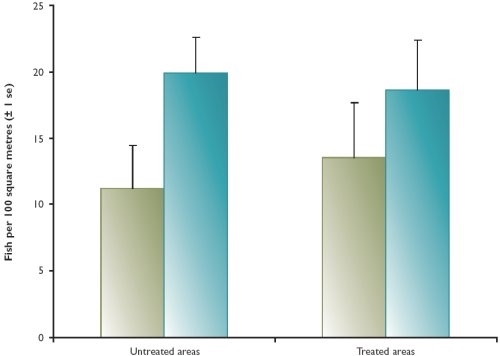

On our River Monnow sites we undertook two years (2003 and 2004) of pretreatment surveys and two years post-treatment in 2005 and 2006. The results of electro-fishing show that numbers of brown trout vary between years but, as yet, there has been no measurable change in numbers of trout fry, parr or older trout due to the treatments on any stream. Figure 2 shows that the mean density of trout fry (0+ years old) per 100 square metres has increased following treatments, but they have also increased in control areas. We found similar patterns between treatment and control sites for other age classes of trout.

Figure 2: Densities of brown trout fry in the Monnow before and after habitat treatments

In addition to counting trout, we have also used HABSCORE to measure the quality of habitat available to trout. HABSCORE is a statistical model developed by the Environment Agency to asses the suitability of habitat for brown trout and juvenile salmon. It takes into account the types of stream flow eg. pool, riffle or glide, substrate characteristics, eg. boulders, cobbles, gravel or silt and stream widths and water depths. It also takes into account the percentage of over-hanging and in-stream vegetation. HABSCORE can be used to predict densities of trout in most age classes.

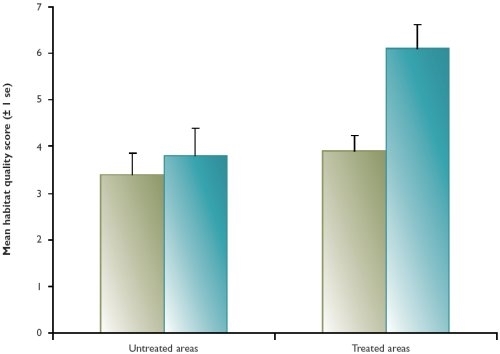

Our results show that HABSCORE values have increased as a result of our treatments (see Figure 3). This indicates that the project has had a positive effect on the trout’s habitat. We hope that trout numbers will begin to respond soon.

Figure 3: Habitat quality for trout of less than 20cm on the Monnow before and after treatment