Key findings

- Lowland woods managed for pheasants had a more open structure than non-game woods and greater cover of herbs and brambles.

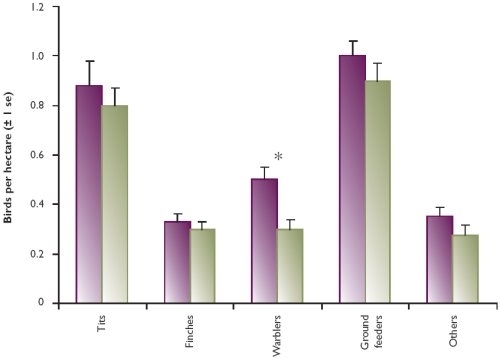

- More songbirds, especially warblers, were recorded in game woods.

- Total deer numbers were greater in game woods, but the relative abundance of deer species and the incidence of browsing were more influenced by region than game management.

- There were no differences in squirrel numbers or activity between game and non-game woods.

Since 2002 we have adopted a range of approaches to assess environmental effects of pheasant releasing. This has included looking at changes in ground flora caused by pheasant poults in woodland release pens and the influence of release density on wildlife biodiversity in the wider countryside. We know from previous research that pheasant shooting provides a major incentive for planting and managing woodlands. However, we have not documented previously how game management influences plants and animals within these woods. For example, in game woods, supplementary feeding, releasing pheasants, shrub planting, skylighting, creation of flushing points and ride and edge management are all common practice. These techniques, perhaps with the exception of ride management, are unlikely to occur in farm woodlands where there is no game interest.

To determine the effect of pheasant releasing and its associated management on woodland biodiversity, in summer 2004 we surveyed 159 woods in two regions: East Anglia and the Hampshire and South Wessex Downs. Half of these woods were managed for game (ie. they each contained at least one pheasant release pen and supplementary feeding took place in winter), whereas there had been no game management in the remaining woods for at least 25 years. We randomly selected about 40% of woods within each treatment group and region from all the deciduous and mixed woodland within each region and the remainder from our existing contact databases. Frequencies of woodland types were comparable between game and non-game woods with about 90% of woods in each group dominated by oak or ash.

Between mid-May and mid-July we measured vegetation cover, dominant species and habitat structure using a point-quadrat method at 40 points over an area of four hectares within in each study wood. We recorded signs of mammal activity (browsing, feeding, droppings) at the same 40 points and counted individuals of each bird species within the four-hectare block. We avoided the woodland edge as this is a distinct habitat and may be the focus of a separate study in the future.

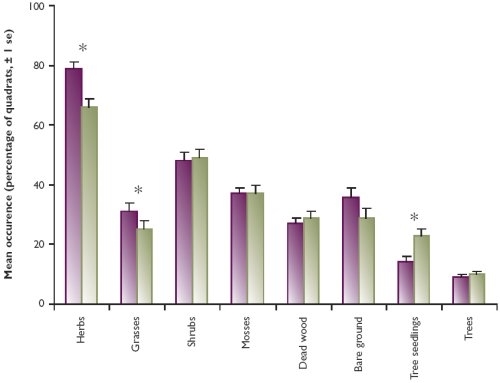

We found that herbs and grasses occurred more frequently in ground quadrats in game woods than non-game woods (see Figure 1), but there were significant regional differences as well (more herbs in Hampshire, more grasses in East Anglia). Analysis of vegetation structure in six height bands revealed a more open canopy in game woods and higher vegetation density up to one metre. There was a higher density of brambles in game woods than non-game woods up to a height of 30 centimetres, but there were no differences between the woods in the abundance of woody shrub species above 30 centimetres.

Figure 1: Frequency of occurrence (% quadrats) of different plant types in woods managed for game and in non-game woods

Figure 2: Average songbirds per hectare in 80 game managed woods and 79 non-game woods

We observed more deer in game woods with more roe deer in Hampshire and greater numbers of muntjac in East Anglia. Signs of deer browsing were more frequent in non-game woods in East Anglia, but more frequent in game woods in Hampshire, possibly reflecting regional differences in the abundance of different deer species and management policies. We need to do further analyses of deer numbers, vegetation structure and bird numbers within each region to understand better the complex interaction between the effects of deer and game management on woodland vegetation and birds. We found no evidence of management or regional differences in grey squirrel numbers or levels of damage.

These results suggest that the interiors of lowland woods managed for pheasants have a more open structure, creating favourable conditions for the growth of herbs and brambles and supporting higher densities of songbird species requiring dense low cover for nesting. Our findings indicate that outside the release pen, impacts of released pheasants on woodland flora and fauna tend to be benign or positive. We need to do further work, however, to assess what may be subtle changes in floral communities and to understand fully the mechanisms by which management for pheasants affects other woodland species.