Glucose key to understanding Hexamita

Key findings

- Transmission is most likely through faecal contamination, not through cysts harboured in the ground.

- Blood biochemistry suggests that the birds are in a state of effective starvation.

- Developing glucose and electrolyte solutions for oral administration may be a way of combatting the effects of the disease.

Hexamitiasis caused by infection with the organism Hexamita meleagridis (Spironucleus) remains the major disease affecting reared game birds. Both pheasants and partridges suffer from this condition although the syndromes observed in the two species differ in some important aspects. The disease is probably the major cause of mortality in gamebirds during the rearing and immediate post-release period.

This article reports on work carried out by Dr Sheelagh Lloyd at Cambridge University Veterinary School during 2003.

From the start, the life-cycle of Spironucleus has remained uncertain, early workers assumed and some reported a cyst-like stage that would allow the organism to survive in the environment between hosts. Such a stage would explain the fact that field reports suggest that some release pens cause repeated problems and others appear disease-free. During our studies, hundreds of faecal smears and smears of the small intestine stained with giemsa have been examined and no cysts have been found.

In limited clinical observations, birds entering pens with damp areas that had housed infected birds 0 to two days previously became infected. Birds did not become infected if the pens had been empty for five days, suggesting that any infective form has a relatively limited survival time outside the host bird. The absence of a cyst is consistent with the fact that Trichomonas, a similar type of organism, does not form cysts and yet readily transfers between gamebird populations. The single ‘cyst’ seen in our early work must have been an artefact. This supports the theory that transmission of the disease is by the ingestion of contaminated faecal material.

In previous years, we thought that there might be some association between several disease-causing organisms. Our findings, however, were not consistent. No other organism has consistently been found in pheasants, tending to confirm the importance of Spironucleus as a primary pathogen in this species. In partridges, however, it seems that birds are far more likely to show disease if they are concurrently infected with Eimeria coccidia.

Throughout our studies, we have been constantly surprised at the apparent lack of pathological changes, even in severely affected birds. Birds heavily infected with Spironucleus tend to demonstrate depression, diarrhoea and severe weight loss, often being described as ‘knife-boned’. Blood biochemistry suggests that the birds are in a state of effective starvation. In the absence of obvious physical damage to the intestine we were interested in studying the absorption across the gut to see if this was adversely affected or could be manipulated to provide a ‘cure’ for the condition.

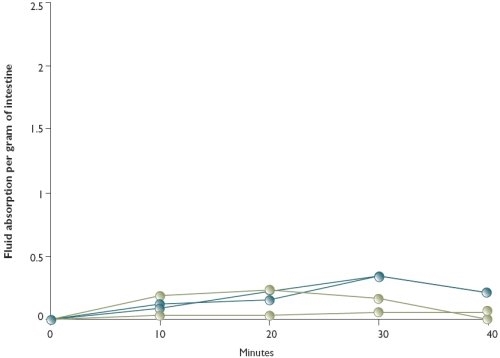

Figure 1: Fluid absorption across four sections of gut from a pheasant severely infected with Hexamita

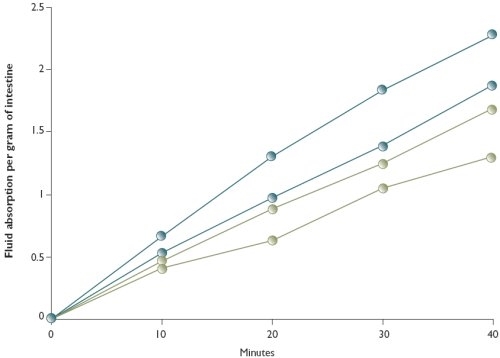

Figure 2: Fluid absorption across four sections of gut from a healthy pheasant

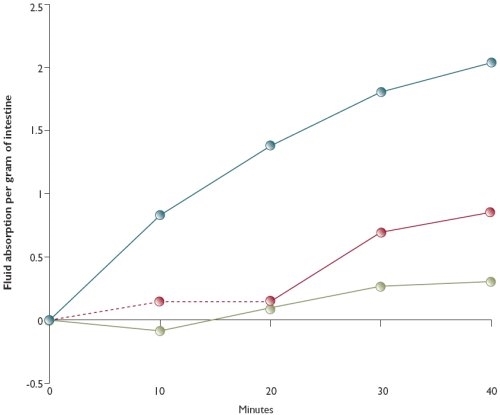

Figure 3: Fluid absorption across three sections of gut from a pheasant moderately infected with Hexamita

Segments from the intestine of birds, taken within minutes after death, were turned inside-out and bathed in a variety of test solutions. The segments were periodically weighed and absorption was measured by the weight gain achieved over time. These studies indicated that absorption of a specially-designed gamebird electrolyte solution was usually poor in very heavily-infected birds (see Figure 1) but good in many moderately to lightly infected birds (see Figures 2 and 3).

By manipulation of the constituents of the fluid, absorption could be altered in both normal and heavily-infected birds. Deprivation of sodium and glucose prevented absorption across the intestine, but doubling the glucose levels was very effective in increasing absorption.

This could be mimicked in both normal and infected intestines deprived of glucose and then incubated in increased glucose buffer. We have long suggested that, at a very minimum, infection with Spironucleus and their associated frenetic activity must deprive the host of vital glucose supplies.

Could this indeed be part of the story? Increasing the levels of the amino acid glycine also appeared to have a good effect, although this needs to be tested further. We hope that this work will lead to recommendations that will greatly reduce the serious losses due to hexamitiasis.

Get the Latest News & Advice

Join over 100,000 subscribers and stay updated on our latest advice, research, news and offers.

*You may change your mind any time. For more information, see our Privacy Policy.