By 1998, in England, only 773 males remained, restricted to the Pennine Hills in northern England, and in 1999 the black grouse was designated a Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) species.

Between 1995 and 2015 a series of focused multi-partner funded projects, led by the GWCT, targeted remaining black grouse strongholds in the Pennines. These initiatives used agri-environment schemes to encourage farmers to restore habitats, including creating pockets of scrubby woodlands and reducing grazing on the moor fringes to improve the insect-rich swards favoured by chicks.

This resulted in initial increases in breeding success, with number of males doubling by 2014 to 1,437. During this period the GWCT also successfully translocated wild males and females into the Yorkshire Dales, establishing new lekking groups and expanding their range south.

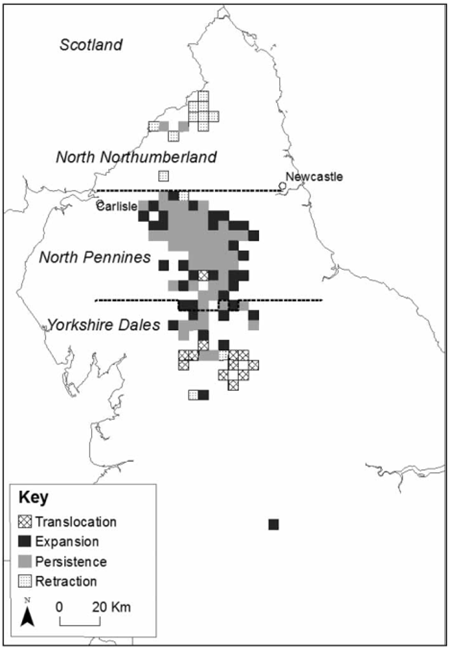

Figure 1: The location of the 5x5km grid squares surveyed in 2014 in north Northumberland,

North Pennines and the Yorkshire Dales, and the other areas surveyed during the Black Grouse survey.

Since then, the English population has stabilised at 1,000-2,000 displaying males.

Despite these encouraging increases, black grouse in England remain severely vulnerable due to their small population and restricted range. GWCT annual lek counts in spring and brood counts in August show that adult survival is generally high, except in harsh winters, but population growth is limited by poor breeding productivity. Poor breeding is linked to high rainfall when chicks hatch in June, lack of insects, and chick predation by stoats.

In 2023 the GWCT successfully applied for funding for a new two-year project and was given a £162,750 grant from Natural England’s Species Recovery Programme.