Key points

- Agricultural intensification is one of the main drivers of declines in invertebrate abundance, with the first decade of the study seeing 65% of insect groups decline. The other principal factor is changes in average spring/early summer temperature and total rainfall.

- Though significant, many of the overall declines in invertebrate numbers in the Sussex Study are less severe than those of other well-publicised studies. The researchers compared results for three groups of insects to other studies – aphids and ground beetles had declined more in the Sussex samples, while butterflies and moths had increased.

- Overall, the total number of invertebrates sampled in the Sussex Study fields declined by 37% from 1970 to 2019.

- 47% of the distinct invertebrate groups studied declined in abundance, whilst 16% increased, and 37% stayed the same.

- Four out of five measures of avian chick-food invertebrate abundance declined significantly.

Background

The GWCT Sussex Study was established in 1968 to investigate the drivers of grey partridge declines. It is the longest-running monitoring project in the world measuring the impact of changes in farming on the fauna and flora of arable land. The survey area focuses on 32 square kilometres of arable farmland in the Sussex Downs.

The GWCT Sussex Study was established in 1968 to investigate the drivers of grey partridge declines. It is the longest-running monitoring project in the world measuring the impact of changes in farming on the fauna and flora of arable land. The survey area focuses on 32 square kilometres of arable farmland in the Sussex Downs.

As well as monitoring numbers of grey partridges, annual data are collected on crop type, field size, weather, crop disease, pesticide use, arable plants, and invertebrates. Since 1970, scientists have carried out invertebrate surveys on the same arable fields, at the same time every year, studying the cropping area rather than nearby habitat features. During the 50-year period in question, an average of 57% of the land was covered by arable fields where a variety of cereal crops (e.g. wheat, barley) and break crops (e.g. oilseed rape, beans) were grown. The last time overall trends in the Sussex invertebrate survey were published was in 1991.

On arable land, invertebrates play many important roles, supporting food production and the farmland ecosystem. These include control of crop pests, improving the health of soil, and pollinating crops, as well as being a food supply for many animals such as farmland birds. Historical and ongoing changes in invertebrate abundance in agricultural landscapes are thought to be driven by several factors, such as climate change, pesticide use, changes in associated semi-natural habitats (such as hedges and field boundaries), and the types of crops being grown.

To understand the impacts of arable land management on invertebrate populations, we need long-term data on a broad range of invertebrate families, collected in the same landscape using the same methods over time and focused on the arable environment itself, not adjacent habitats.

What they did

Every year the scientists visited each cereal field in the study area, in the third week of June, and collected an invertebrate sample using a ‘D-Vac’ suction trap to hoover up small invertebrates from the vegetation layer.

Every year the scientists visited each cereal field in the study area, in the third week of June, and collected an invertebrate sample using a ‘D-Vac’ suction trap to hoover up small invertebrates from the vegetation layer.

Invertebrate samples were cleaned and preserved, then identified. A total of 2.98 million invertebrates were collected during the study period, from a total of 4,757 samples – an average of 95 samples per year.

The invertebrates in the samples were sorted and grouped in multiple different ways:

- As taxonomic groups (e.g. aphid, fly, beetle)

- As functional groups (e.g. pollinator, crop pest)

- As life stages (e.g. pupa, adult)

- As components of farmland bird chick-food indices (e.g. for grey partridge, skylark, corn bunting, yellowhammer)

The scientists used statistical models to identify trends and relationships in the invertebrate data and farming characteristics over time.

What they found

Overall, between 1970 and 2019, invertebrates sampled in the Sussex Study declined by 37%. The results showed that 47% of invertebrate taxa declined in abundance, 16% increased and 37% stayed the same.

Fungivores, herbivores, predators, parasitoids and dung-eaters declined significantly. Four out of five measures of avian chick-food invertebrate abundance declined significantly, and aphids declined by 90%. There was no detectable change in pollinator numbers but many pollinator groups, such as bees, are not normally associated with arable fields and do not appear in samples taken.

The six most abundant invertebrate groups recorded in the Sussex Study samples were springtails, aphids, flies, thrips, parasitic wasps, and beetles.

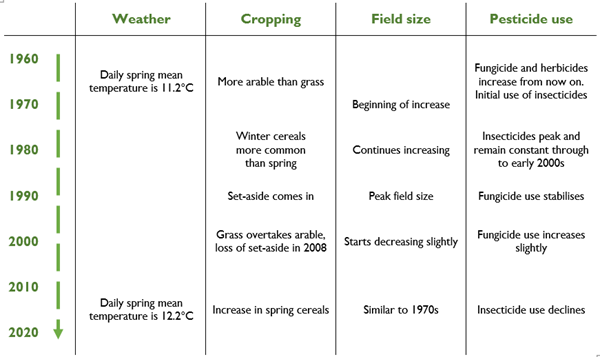

Considering the five decades that were covered by the study, there were more declines in the first decade of the study period 1970 to 1979 (65% of taxa) when both pesticide use and field size were increasing. Insecticide use was highest between the late 1980s through to the early 2000s and has declined over time. Changes in agricultural and weather variables are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Summary of the agricultural and weather variables at the Sussex Study during the study period

What does this mean?

The findings of this research are difficult to compare to other work because the GWCT Sussex Study is unique; the invertebrate communities here have been studied on the same land, at the same time of year, using the same methods, for 50 years. However, the findings are in keeping with a 2014 study that showed a 45% decline in global insect populations over 40 years, but less severe than those of a 2017 study of German nature reserves where flying insect biomass declined by 75% over 27 years.

The findings of this research are difficult to compare to other work because the GWCT Sussex Study is unique; the invertebrate communities here have been studied on the same land, at the same time of year, using the same methods, for 50 years. However, the findings are in keeping with a 2014 study that showed a 45% decline in global insect populations over 40 years, but less severe than those of a 2017 study of German nature reserves where flying insect biomass declined by 75% over 27 years.

The latest results highlight declines in groups other than the high-profile butterflies, moths and bees, including beetles, aphids, flies and parasitic wasps. The abundance of pollinators (excluding bees) in the study areas has remained stable despite national declines.

The changes seen in the invertebrate community at Sussex are explained, in part, by changes in crop types, field size, pesticide use, and weather. This is in line with a large body of research, which suggests that climate change and intensification of agriculture are major drivers of changes in invertebrate abundance. Very dry or very wet conditions, brought about by weather pattern changes, can have a negative impact on invertebrate species.

Where efforts are made to restore invertebrate abundance, it is likely there will be a time lag before results are seen. Reversing the declines of invertebrates that are sensitive to agricultural intensification will require widespread participation in agri-environmental schemes, decreasing field sizes, and overall reduction of pesticide use.

Declines in the abundance and diversity of invertebrates around the globe have been widely reported in recent years. There are serious concerns about the impact of this loss on the world’s habitats and natural processes, and how this is affecting human civilisation. More research is needed into how to address invertebrate declines and still ensure productive and profitable farming. Provision of habitat options such as perennial seed mixes to encourage insects and further development of integrated pest management options will help.

For more information on the Sussex Study Paper via an Ecological Continuity Trust webinar, watch this video:

Read the original paper

J. A. Ewald, G. R. Potts, N. J. Aebischer, S. J. Moreby, C. J. Wheatley, and R. A. Burrell (2024). Fifty years of monitoring changes in the abundance of invertebrates in the cereal ecosystem of the Sussex Downs, England. Insect Conservation and Diversity.