Key findings

- After 30 years of decline, brown hare numbers are showing promising signs of recovery by 2006.

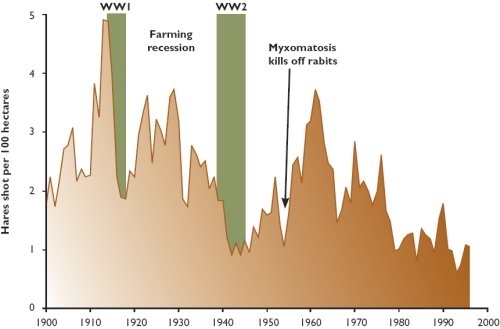

Of our mammal fauna, the brown hare is perhaps the most suited to cultivated land. It rarely frequents woodland or hedgerow, but opts for open arable and pasture. It was rather surprising therefore that during the farming boom times of the 1970s hare numbers showed clear evidence of a decline. There are few schemes that have monitored the abundance of mammals over long periods and, for the hare, the best data come from the game books of shooting estates. Although such books obviously record the numbers of hares that have been killed, not the number alive, they are quantitative records and, in some cases, they can go back for over a century. When combined, such game books can give a long-term track of the hare bag.

Bag records of hares from an average of 12 England lowland estates from 1900 to 1996

This track indicates that:

- In Edwardian times hares were about twice as common as they were in the early 1990s.

- Hare numbers slumped between the world wars during a period of farming recession when cereal cultivation dropped from three million hectares to under two million.

- There was little or no formal shooting of any game during the wars probably because most gamekeeping was given up.

- With the re-establishment of gamekeeping hare bags recovered.

- Hare numbers peaked in 1961, because of the absence of rabbits following the Myxomatosis epidemic.

- There was a 30-year decline in bags at least until the mid-1990s. This was caused mainly by the abandonment of traditional mixed farming in favour of modern methods.

This hare decline was also found in Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and Hungary and, later, in Poland. It paralleled a loss of farmland birds including the grey partridge.

In 1995, following The Convention on Biological Diversity (1992), the UK set up a broad-based Biodiversity Action Plan to recover the status of a range of wildlife. The brown hare was chosen as one of these species and its Action Plan aimed to double the then population by 2010 and maintain its geographic range. The main actions called for improving uptake of agri-environment schemes, reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), and better use of set-aside. The Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust and the Mammal Society became joint lead partners for the plan.

In the decade since then there has been significant progress in conserving farmland wildlife. In particular there have been radical changes to the CAP. First, the arable area was reduced by making set-aside mandatory. Later, support shifted from production to a crop-area based payment, and finally to land-area support with a sizeable proportion siphoned off for environmental schemes.

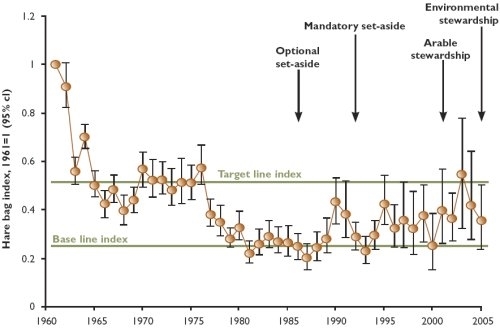

Superimposing these events onto the recent changes in the hare bag it looks as though they may be helping to restore hare populations. Indeed, if the use of bag records is a direct indicator of hare numbers then the figure below suggests that we may be about halfway to achieving the biodiversity target of doubling numbers by 2010.

National Gamebag Census trend for brown hare 1961-2005

The graph shows base line and target levels for the Biodiversity Species Action Plan, as well as significant Common Agricultural Policy measures that may have helped to reverse the trend since the mid-1980s.

This may appear wishful thinking, but there is supporting evidence. The National Gamebag Census is now part of a collaboration with other organisations under the Joint Nature Conservation Committee's Tracking Mammals Partnership. Within this partnership two other schemes have recorded increases in hare numbers in England in recent years - these are the British Trust for Ornithology's Breeding Bird Survey and its Waterways Breeding Bird Survey. Further, as we reported in our Review of 2003, the East Midland farms that adopted measures under the trial Arable Stewardship Pilot Scheme, set up in 1998, showed improved hare numbers by an average of 35% compared with farms that did not join the scheme.