As the rate of climate change accelerates, so too does the rate at which climate-related records are surpassed. The 2015/2016 winter has gone down in history as the second wettest UK winter since records began, beaten only by the 2013/2014 winter. January 2014 was the wettest month in almost 250 years. This followed an appallingly soggy 2012 that was (at the time) the second wettest year on record. Some might seek solace that the wettest year on record was decades ago. Sadly not: the wettest year on record was in 2000.

To cut a long story short, four of the UK’s five wettest recorded years have occurred since 2000 (in order of wetness: 2000, 2012, 2008 and 2002).

It seems that long-term woodland destruction, urbanisation, loss of lakes and ponds and modifications to natural river channels have literally cleared the way for a torrent of water to cascade unabated into lower river catchments. And this happens so quickly that there isn’t time for drainage systems to cope. Flooding ensues and endures.

Whilst their effect on human inhabitations is all too obvious, we are not the only species to be affected by floods. Fish inhabit the very rivers that are bursting their banks onto the surrounding towns and countryside. Unlike humans, however, fish have been experiencing floods in their native river habitats for hundreds or thousands of years. And because floods present a strong evolutionarily selective force (you adapt or you die), fish have adapted to survive and even thrive under certain flood conditions.

Salmonids are a good example of a group of fish species that have adapted to local flow regimes, inhabiting a range of rivers from those in Scotland with highly variable flows and high-gradient channels to shallow and stable slow-flowing chalk stream in southern England.

Understanding how floods affect salmon is complicated by three unavoidable factors:

- Floods will affect different salmon life stages, such as eggs and adults, differently

- Floods of different characteristics, such as timing and duration, will affect each life stage differently

- Our ability to study salmon movements and behaviours under flood conditions is impacted by turbid waters and reduced equipment efficiency or malfunction

The interactions between the first two complexities have not been well studied, perhaps because floods are rare events and studies to understand the effects of flood characteristics on different salmon life stages will suffer from too few observations. Instead, research has tended to examine the influence of a single measure of flow on a specific salmon life stage and its variation.

A factor that limits the distribution of salmonids is availability of useable spawning gravels. One can imagine that floods are good for salmonids if they allow them to reach otherwise inaccessible spawning grounds. Here, however, the trouble comes if the redds (egg nests) are exposed to environmental stress when the water recedes: the instinct to seek suitable gravels high in the river channel could prove a poor adaptation if the channel then dries in spring, causing the eggs to die – a type of evolutionary trap. However, if the flood duration were sufficient to maintain suitable redd conditions, then these otherwise inaccessible spawning grounds could prove to be highly productive.

One of the most sensitive salmonid life stages is the egg. Salmonids lay their eggs in gravels, in part, to protect them from adverse environmental conditions, such as high flows. Under flood conditions, high velocity water can wash eggs out of redds causing them to die. This is particularly true for grayling that lay their eggs shallow in redds. This is also more likely in rivers with hard bedrock that tend to react quickly and fiercely to rainfall events. On the other hand, a comparatively low magnitude or long duration flood could wash sediments out of redds that would otherwise asphyxiate the developing eggs, thereby improving egg survival.

If eggs survive the floods, then they emerge as fry. Fry tend to stay in the shallow and protected waters at the edges of river channels to avoid predators and because they are not strong swimmers. High flows during, or shortly after emergence has been associated with high fry mortality – they too can be washed out of the river and die, whether down the river channel into saline water or over the edge of the channel onto adjoining land. However, fry swimming ability increases quickly with size and so the timing of the flood is critical to fry survival.

Summer floods are perhaps less common and so their effects are even less well understood. One factor thought to affect the growth and development of juvenile salmonids is the number of other juvenile salmonids, through density dependent growth: as the number of juvenile salmon increases, so the area available for each individual to find food and grow decreases. Assuming density dependent growth, then a summer flood that increases the wetted area of the river might convey increased growth rates and better conditioned juveniles with a higher chance of survival. With their improved swimming ability compared to fry, juveniles are less susceptible to washout during floods.

Once beyond the juvenile stage, the effect of flow on salmon and sea trout becomes important for migration timing. Flows facilitate the downstream migration of smolts. High flows and associated turbidity could increase the rate at which smolts migrate out of the river in murky water, both of which will help to lessen the risk of predation.

When it comes to re-entering the river as a spawning adult, then flow again appears to be a trigger, although the exact nature of the relationship between flow and migration timing has proven elusive:

- It is not clear whether they move on or after floods (or freshets) or, indeed, whether they are even present in the river mouth at the time of floods

- There is high inter-river variability; for example, flow might be less influential on chalk streams with more stable flow conditions relative to granite rivers.

Once in the river, salmon migration occurs in three phases:

- The upstream migration phase

- The spawning ground searching phase

- The spawning site holding phase

Of these, phase 1 is the most affected by flow. The speed of upstream migration seems to increase with increasing flow, although in floods the salmon may stop moving and be forced to take refuge. Again, the exact timing of these different phases is likely to be associated with floods or freshets, but the precise nature of that association remains elusive.

It seems clear that flooding can affect salmonids in many ways and developing an understanding of the interactions and trade-offs will require the use of high-quality, long-term (or well-replicated) datasets that are difficult to collect in aquatic systems. Fish cannot simply be counted like birds because they can’t be seen without additional apparatus. This is further complicated because water is corrosive, conductive and carries debris and huge energy, particularly during flood conditions.

At East Stoke, on the River Frome in Dorset, the GWCT has been monitoring adult, smolt and parr salmon for the last 44, 21 and 16 years, respectively. To do this, we use a range of monitoring equipment, including a resistivity counter, a 24-hour video surveillance camera and a system of electronic tag-reading devices (approximately 10,000 juvenile salmon are marked with electronic tags each year). For the large majority of the time, this equipment does an excellent job of detecting migrating salmon. Rarely, however, when flow conditions are extraordinary, such as under major flood conditions, the efficiency of the equipment is compromised.

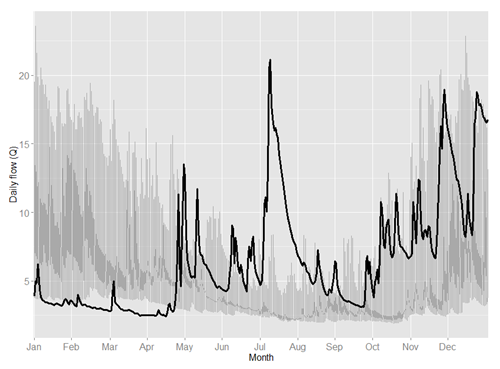

Take the spring and summer floods of 2012 as an example. Daily flows from the end of April to the end of September were unprecedented among records dating back to 1992 (Figure 1). These extraordinary flows forced us to lift our electronic readers on the East Stoke salmon counter (Figure 2) and reduced our resistivity and video counter efficiency. Consequently, we reported a minimum adult salmon count in 2012. Also, because the floods began at the end of April, they impinged on our ability to quantify the migration of smolts from the river, which usually ends in late April or early May.

Figure 1: Daily flows for 2012 (black line) compared to flows for years 1992 to 2011 (grey lines)

Figure 2: The East Stoke fish counter under normal flow conditions in 2010 and under flood conditions in 2012

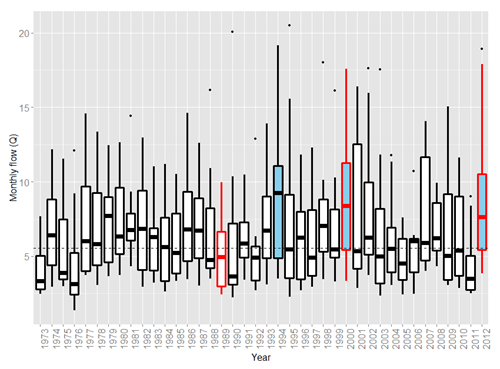

Despite sometimes treacherous conditions, there are only three other years when we have reported a minimum adult salmon count. Figure 3 shows that we have recorded three years with extraordinary high median monthly flows (1994, 2000 and 2012). In two of these years – 2000 and 2012 – we reported a minimum adult salmon count. In contrast, we were able to produce an accurate count in 1994, despite the extraordinary flow conditions. This highlights two points:

- That we can produce counts under flood conditions but they might be less accurate

- There might be times when our counting system malfunctions for reasons other than flow, in which we can produce only a minimum count, such as occurred in 1989 (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Boxplots showing monthly flows for each year and highlighting those years for which (1) we were unable to produce an accurate adult salmon count (red box), and (2) the river was in flood (blue fill). The dashed line is the mean monthly flow excluding flood years

With growing evidence that we’re being propelled ever faster towards the wetter and warmer winters predicted by climate change scientists a decade ago, we’ll have to find ways to cope with flooding and the effects it will have on our salmon and grayling monitoring programmes. We need also, however, to be mindful of the effects on our salmonid populations and our ability to monitor them during drought conditions, which are forecast to become more frequent and intense.

One of the ways in which we are attempting to do this is statistically. Within the MorFish project, we designed a statistical framework that allows us to use information from periods when the salmon counting system is operational to predict what the salmon count was likely during periods when the system is malfunctioning. In addition, the analysis uses observations to learn about the system efficiency under variable flow conditions and use that information to improve estimates during periods of low efficiency. Finally, because floods are associated with other environmental factors, e.g., increased turbidity, we aim to extend the framework to investigate whether these additional factors will change our salmon count estimates.

It is hoped that these analyses will deliver useful information on the effects of extreme flows (droughts and floods) on the health of salmon – and more generally, fish – population dynamics. What we then do to manage flow regimes are decisions that will need to be made at a local scale, since flow regimes are tied into many local factors, including geology, river-specific hydroecology and hydromorphology and – of course – abstraction regimes. Certainly, the answer will lie in maintaining the ecological integrity of the river. One step to doing this will be to understand and encourage its natural hydrological variability, both seasonally and interannually, an approach known as the ‘natural flow paradigm’.