By Francis Buner, Senior Conservation Scientist

By Francis Buner, Senior Conservation Scientist

In my last blog I provided an overview of the breeding and wintering birds at Rotherfield based on a simple bird list. One could of course argue that the list was a rather comprehensive one, as it was based on five years of intensive bird monitoring across most months each year.

Additionally, it stated whether each species was recorded breeding, on passage or wintering. Nevertheless, at the end it essentially remained a simple bird list like most birders in Britain would keep in their field notebooks.

Having said that, comprehensive bird lists are the first step towards understanding the avifauna of a particular place or area and therefore, do have their uses. In case of the Rotherfield demonstration project area, the list informed us about the impressive diversity of birds found there, but also about the species that are absent.

Personally I find that already quite interesting, don’t you? Nevertheless, the species list told us nothing about how many individuals of each species the project area supports. In other words, how abundant they are, nor how their numbers might have changed over time. This is when it gets really interesting.

In our case, it would of course be interesting to know how the management prescriptions put in place to bring about the recovery of the grey partridge, benefit other farmland birds. While a simple bird list doesn’t tell us much in that respect, bird abundance indices collected over several years do.

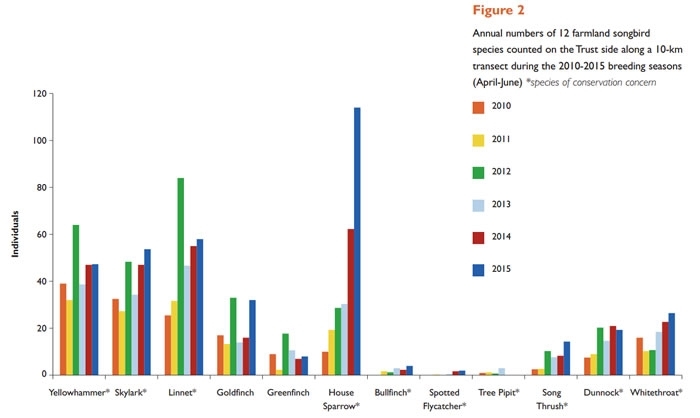

To get the information needed, we have monitored farmland birds along a 10km farmland transect every March, April and June since 2010. And what is the result?

Since the project begin, the total number of farmland birds of conservation concern that are found breeding in the area managed by the Trust has increased an impressive 2.3-fold. Now, where else in Britain have farmland birds more than doubled?

Not at many I should think. Nationally, almost all farmland bird species continue to decline. Somewhat surprisingly, the biggest winner at Rotherfield to date is the house sparrow which has increased an incredible 11.4-fold!

Some of this increase might be due to improved monitoring at their colonies (sparrow numbers are chronically difficult to estimate and we believe we might have unwillingly got better at it during the course of this project!). Nevertheless, across the whole project area we estimate the total number of house sparrows to be more than 1000 individuals during mid-summer.

The species with the second highest increase is the song thrush (5.7-fold increase), followed by a 2.6 increase of dunnocks, 2.3 for linnets, 1.9 for goldfinches, 1.7 for skylarks, 1.6 for whitethroats (the BTO reports a nation-wide increase of this species) and 1.2 –fold increase of yellowhammers.

The species with the second highest increase is the song thrush (5.7-fold increase), followed by a 2.6 increase of dunnocks, 2.3 for linnets, 1.9 for goldfinches, 1.7 for skylarks, 1.6 for whitethroats (the BTO reports a nation-wide increase of this species) and 1.2 –fold increase of yellowhammers.

Greenfinch numbers had doubled by 2012 but have since fallen back to levels in 2010, mirroring the national trend, likely due to the parasitical protozoan disease trichomonosis. Bullfinches and spotted flycatchers are being recorded at low but stable levels.

We are particularly proud of the few breeding tree pipit pairs, and although they are small in number, their presence is not irrelevant. Tree pipits are quite rare in Hampshire. Sadly, the species disappeared from the core area in 2015, likely as result of the nationally recorded decline last year by the BTO, who believe that negative factors influence this species at its African wintering sites.

However, I’m happy to report that this year, the tree pipit is back in the core area with two pairs and four pairs across the whole project area.

Putting this into simple words, this means that if farmland habitat is restored to a level that suits grey partridge recovery, assisted by predation management, the increase of farmland birds in general can be very impressive indeed.

Why not try it in your own area? Please feel free to contact us as it’s not quite as simple as it might sound. We are always happy to share some useful tips and tricks…

Whitethroat picture by Markus Jenny.

Please support our vital work at Rotherfield