By Henrietta Appleton, GWCT Policy Officer (England)

The value to society of the organic carbon stock in our soils is the subject of much interest as we seek to move towards net zero. Whilst reducing emissions from non-replaceable sources of carbon must remain the focus, complementing this with increasing the sequestration potential of our land uses will help compensate for those emissions that are unavoidable whilst also delivering a range of other benefits.

But in the case of soils is the tail wagging the dog? In other words is the focus on carbon distracting from the benefits of considering soil health in the round.

The carbon content of soil equates to its organic matter; organic matter being the part of the soil that is made up of dead or decaying plants or animals and dead microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi. In simple terms, those soils with high organic matter content such as peats have high soil C whilst those with low organic matter content such as sandy soils will have low soil C – and have difficulty sequestering more as they will have a low saturation point.

An often-overlooked value of this organic matter is that it is the food that supports the micro-organisms that make up the soil ecosystem. It is these micro-organisms that underpin the health of our soils through breaking down organic matter, releasing and cycling nutrients and improving soil structure including moisture retention. The healthier the soil the more active the micro-organisms are – and ironically the more carbon that will be released as they breakdown the organic matter.

Our last APPG considered whether you could measure soil carbon and in simple terms concluded that perhaps you shouldn’t be trying! Firstly, whilst there is much focus on the organic matter content of our soils, carbon only accounts for around 50%; the other half consisting of nutrients.

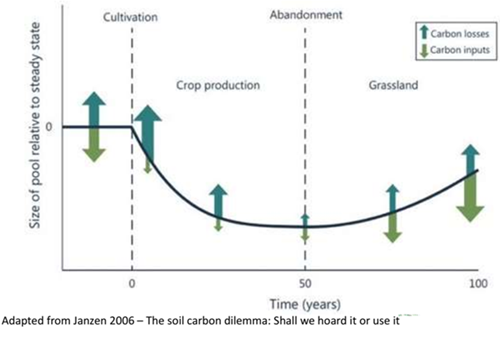

Secondly, although soil carbon can be enhanced through reducing cultivation processes and ensuring continuous cover all year round, each soil type has a saturation point which limits the absolute stock that can be held. In addition, soil carbon does not increase indefinitely, and any increase is not permanent; it is reversible. For example, during the course of a crop rotation the amount of soil carbon will change depending on whether you are at the start of the cycle, halfway through or at the end as the graph below demonstrates.

Furthermore, our work has suggested that soil carbon only really starts to accumulate after about 10 years and that reduced cultivations can, under some conditions, result in increased nitrous oxide and methane emissions, which have a bigger impact on our climate in the short term.

These points aside one of the biggest concerns is ensuring that any ‘additional’ carbon is not simply ‘redistributed’ carbon. This is vital if actions are to mitigate climate change. To truly create ‘additional’ carbon (i.e. carbon credits) there must be a transfer of carbon from the atmosphere to soil. Some actions being promoted do not achieve that.

For example, the use of organic manures is merely the redistribution of carbon within the landscape i.e. from one farm to another (although the traditional mixed farm is an exception to this) whilst reduced deep cultivations (ploughing) is simply redistributing the carbon within the soil profile (although losses are lower over time so there is some net accumulation). These concerns mean that some claims about the role of soil carbon within agricultural soils are unrealistic as only small increases are possible.

So given this variability and uncertainty, should soil carbon be considered a reliable metric?

Recent agricultural practices involving deep cultivations annually have affected the microbial cycle within soils; the loss to soil health being compensated by inorganic additions. Concerns about the impact that this style of farming is having on soil health and the carbon cost of inorganic nitrogen-fertiliser and cultivations is resulting in the reappraisal of soil management.

The GWCT has long advocated the need to focus on soil health (see blogs in March 2020 and January 2021) based on our research at the Allerton project into what constitutes a healthy soil and how to measure constituents such as soil moisture (see March 2021) as well as research considering the role of soil in crop production “in the round” i.e. from both a sustainable and profitable perspective (e.g. the SoilCare EU project of which we are partners).

Consequently instead of focussing on just one element, soil carbon, we would suggest that the focus should be on payments that support soil health and a reduction in inorganic nitrogen inputs. The former would increase resilience to climate change (for every 1% increase in organic matter, the soil can hold over 200,000 more litres of water per hectare) whilst improving our nitrogen use efficiency would reduce carbon emissions (from its manufacture); both together would support more sustainable food production.

A win-win!