By Henrietta Appleton, Policy Officer (England)

Whilst there was much to be positive about in the recent announcement by the Defra Secretary of State on the 2024 SFI offer in terms of its support for farming (see Comprehensive new SFI scheme a big step forward – the GWCT response), we are disappointed that the opportunity was not taken to include measures in the Environmental Land Management Scheme (ELMS) to reduce predation pressure to facilitate species recovery.

Before you point out that there are options “to control and manage predators of threatened species”, the concern is that this is very limited in its extent. It only covers grey squirrels (which can predate small woodland birds’ nests and obviously impact on red squirrel conservation), American mink (which predate water voles and waterbirds) and the edible dormouse. There is no acknowledgement of the impact that legal control of predation by fox, carrion crow and magpie can have on the recovery of many of our native birds and mammals, including several birds of conservation concern (BoCC).

This is an opportunity missed.

If government is committed to reversing species declines by 2030 then all the causes of their declines need to be addressed. It is not sufficient, or arguably ethical, to just support one aspect – namely habitat.

Wildlife in general will benefit from improvements to habitat, a need that is now effectively supported by ELMS through options such as new hedgerows, winter bird food and pollen and nectar mix for farmland species, nesting plots for lapwing and stone curlew, and the creation/management of wet grassland for waders. But whilst habitat provides the foundation for species conservation, many species benefit from predation management. This includes BoCC such as lapwing, curlew, skylark, yellowhammer, stone-curlew, redshank, song thrush and grey partridge, to name a few.

What makes the absence of options that acknowledge the need for reducing predation pressure a particular conundrum is the fact that such actions are supported by other government conservation policies such as the application of GL40, the general licence to kill or take certain target species of wild birds for the purpose of conserving wild birds.

In addition, for some species the effective provision of habitat through ELMS without the accompanying need for protection from predation has the potential to create a population sink – and therefore is arguably unethical. Providing 5* habitat is likely to attract in the target species, only for them to be killed by legally controllable predators. Should we really be using public money in a way that actually supports species decline? Whilst controlling one species in support of another is not always acceptable to the public, we believe that where it is scientifically proven and justified then conservation values based on science need to trump public values based on emotion.

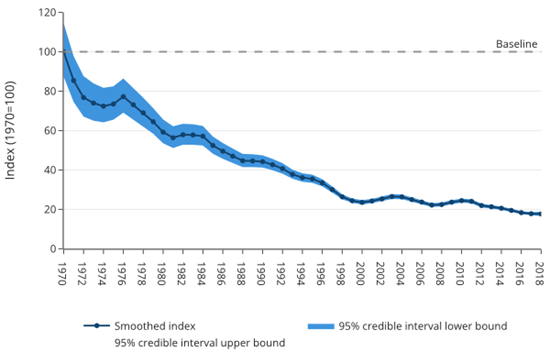

Relative abundance and distribution of priority species in England

Source: https://oifdata.defra.gov.uk/themes/wildlife/D6/

In addition, we question for some species whether the habitat-only approach to their conservation is actually delivering value for money for the public purse. Clearly the costs of funding these measures are not delivering the outcomes desired – as is evidenced by the continual decline in priority species abundance (see graph). The total cost of agri-environment schemes to the UK public purse to 2019 was c£8.5bn (Defra 2020).

At a more detailed level, it has been estimated that approximately £23 million a year is spent on options to support breeding waders on grassland. Yet our work in the Avon Valley demonstrates that the long-term decline in breeding wader populations continues despite government support for habitat. Lapwing breeding success in the Avon Valley was too low at 0.49 chicks/pair to maintain a stable breeding population when habitat measures alone were employed. However, a targeted landscape-scale project to reduce predation pressure during the breeding season alongside improvement to the habitat saw this increase to an average 0.82 chicks/pair – above the threshold 0.7 chicks/pair for a sustainable population.

Why is such evidence being ignored?

One can only guess at the answer to this question. Perhaps the more important question that needs to be asked is “Why are declines still occurring given the considerable amounts of public money invested?” And the answer to that is that more of the same is not enough and reducing predation pressure during the breeding season for many of our native species must become part of ELMS.

This is a point we have been making for a long time – only to have it fall on deaf ears. The reason for raising this now is that time is getting short to achieve the 2030 target, and for some species that do not breed until year three such as the curlew, the time has come for boom or bust decisions. The GWCT produced a report for Defra in 2022 setting out how predation management to aid priority species recovery could be incorporated into and delivered via ELMS. At the time it landed very well with Defra. To reiterate our message, I’ll end by using the final paragraph from a blog I wrote in 2021:

“This government has been world-leading in many new initiatives. Now is the time for it to step up to the challenge and encourage a range of conservation measures that address the different pressures that our wildlife is facing, including habitat improvement and connectivity, but also scientifically-proven measures such as controlling predators before we miss another target and see more species on the brink of extinction.”