By Henrietta Appleton, GWCT Policy Officer (England)

Using the term ‘killing’ rather than ‘management’ would not be my choice when discussing the merits of removing one species to protect another. But I chose it here as it refers to the headings of two recent articles in the Guardian that demonstrate the value of control – She kills to be kind: the mastermind ecologist eliminating invasive predators (10 September) and ‘No easy answer’: the endangered owls that can only be saved by killing other owls (7 October). Both epitomise the challenge that conservation has in addressing public values and attitudes towards the management of pests, invasive species and native predators.

Using the term ‘killing’ rather than ‘management’ would not be my choice when discussing the merits of removing one species to protect another. But I chose it here as it refers to the headings of two recent articles in the Guardian that demonstrate the value of control – She kills to be kind: the mastermind ecologist eliminating invasive predators (10 September) and ‘No easy answer’: the endangered owls that can only be saved by killing other owls (7 October). Both epitomise the challenge that conservation has in addressing public values and attitudes towards the management of pests, invasive species and native predators.

Conservation Through Elimination

The first article focused on the elimination of invasive species that predate on or compete with native, endangered species. As the article said this approach, which began in New Zealand, has been employed throughout the world, including the eradication of rats on Lundy Island in support of puffins and Manx shearwaters. Although there was some opposition to the removal of rats from the island, the resulting increase in the population of the seabird colonies on the island is testament to the need for this to happen.

Public Perception of Species

However, I would hazard a guess that if the subject of the cull had been a different species from the rat, which is generally regarded as a pest, the objections might have been a bit stronger. For example, some may feel that rats should be afforded less protection than, say, grey squirrels, although both are non-native and have implications for biodiversity.

The implications of the public’s perception of the value (or not) of some species over others was a concern we expressed during the passage of the Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act, which set up the Animal Sentience Committee. This perception can influence what is acceptable and what is not in conservation.

The conservation of the water vole is a good example where the public accepted the need to control the American mink to protect ‘ratty’ from extinction. The removal of stoats from Orkney (where they were not present until circa 2010) is another example of the acceptability of the eradication of an ‘invasive’ threat to native species.

When Conservation Demands Sacrifice

The eradication of non-native invasives is fairly clear cut if native species are at risk (from predation or disease). But when is it acceptable to kill one wild native species in an attempt to save another? As the second article says, there is “no easy answer”. This is where our love of nature has to learn from the subject itself if we are going to protect it against anthropomorphic pressures.

The natural ‘food chain’ sees one species higher up the chain ‘feed’ on the more abundant species below. But humanity has challenged this relationship in many ways – by changing habitats through using land to maximise the production of crops for food or fuel; by preying on some species but not others (hunting); by domesticating species; and by the demands of our increasingly consumption-driven lives (roads, factories, power stations and power lines, settlements, etc). Arguably where we are the agents of change, we have a duty to address the problems we have created, such as managing a ‘subsidised’ predator population.

Balancing the Scales

Some species have been able to adapt as their environment changes (termed ‘plasticity’), but in others the removal of a particular habitat type (e.g. low input cereals or native grasslands) or a food source (e.g. invertebrates or wild flowers) means that populations have declined.

Part of our conservation strategy requires us to understand where the ‘break in the chain’ is and how to mitigate it. This has resulted in the design of agri-environment schemes to provide suitable ecological conditions for plant and animal species across the landscape.

The Thin Line Between Conservation and Predation

But the other, less palatable part is to re-balance the impacts of natural predation on a declining bird or animal population. In simple terms, let’s assume a population of 100 birds (or 50 pairs). Given that some, say 20 birds or 10 pairs (20%), will be lost to predators, we can reasonably expect the population to sustain these losses and produce enough young to more than compensate. But if the population is only 50 birds or 25 pairs and the level of predation remains the same i.e. 10 pairs, the loss of 40% may be too great for the production of young to compensate and the population will continue to decline.

Conservation and the Predation Dilemma

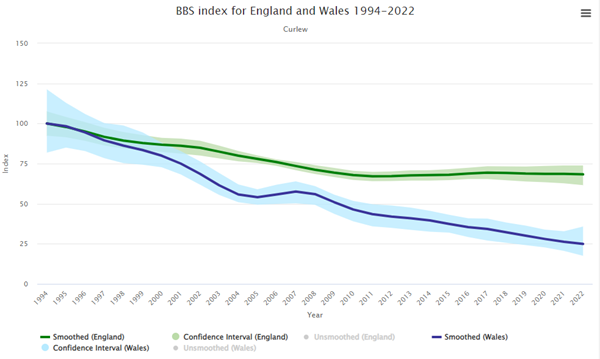

So if we ask ourselves at what point is control acceptable? Or at what point does a proportionate response become appropriate? Then the simple answer (although nothing is ever simple in nature!) is that it is when the losses to predation outweigh the gains from the production of young. This situation has been reached in a number of cases, most significantly amongst our declining ground-nesting wading birds such as the curlew.

The Role of Conservationists

The comment that the “fierce love of birds … helped turn her into one of the conservation world’s great mass killers” (Guardian, 10 September 2023) is very relevant here. So often those who control one species to protect another are seen as nature’s enemies (a throwback to the Victorian/Edwardian era when the implications of such an approach were not fully understood and predator control could be excessive). But, in truth, many of the land managers who undertake predation management are fervent lovers of our nature.

The situation in Wales, for example, where humane-cable restraints (HCRs) have now been banned, means that many are lamenting the very real likelihood that future generations will not hear the iconic call of breeding curlews in that country. There is a very real fear that the Scottish Government will follow this lead – no doubt resulting in significant pressure on England to follow suit.

Ethical Considerations in Predation Management

Conservation strategies must consider not only when is it acceptable to manage one species to protect another, but also how you do it. Interestingly, NatureScot’s position on Wildlife Welfare establishes the principle that death in itself is not a welfare issue; what is important is the manner in which an animal dies to avoid suffering.

The methods of predation management that produce the negative headlines are (usually) those from the past; where they are not will usually be down to poor practice. Hence the GWCT’s call for the licensing of HCR use based on the attainment of a qualification and training. The modern-day tools of HCRs, spring traps and corvid traps have all passed stringent international standards for animal welfare. But the how is not just the tools and their application; it is also the strategy undertaken.

The evidence from two recent research papers by the GWCT and RSPB on curlew conservation underline the importance of an effective and targeted strategy, a point we emphasised in this previous blog.

The RSPB paper concluded that the limited management of predators (fox control by rifle and Larsen traps for crow control) was highly unlikely to be effective for curlew conservation. HCRs were not used on ethical grounds. In contrast, the GWCT paper showed the great value to curlews of predation management as undertaken on grouse moors, which involves the full suite of legal humane predator control methods.

For example, specifically on the Berwyn (in North Wales) paired sites, those on which predation was managed raised chicks at a higher level of productivity (0.93 chicks per pair) than that required to sustain curlew populations (0.48-0.62 chicks per pair).

This level of success was acknowledged in the RSPB paper, which stated: “To date, no published study conducted outside grouse moors has been able to replicate the magnitude of response of breeding waders such as Curlew to interventions on grouse moors.” Yet we can also point to examples away from grouse moors such as on lowland farmland in the Avon Valley, where such an approach has aided other breeding waders such as lapwing, or on Elmley Nature Reserve in Kent.

The GWCT believes that if you are planning to do something, do it well or not at all, particularly as you are taking one life to protect another. A point emphasised in this recent GWCT blog post by our head of predation research, which also considers the role they play in wildlife research.

Evidence-Led Conservation

In addition, the GWCT Think Piece on predation management provides a balanced and informed explanation of its necessity and covers the scientific detail behind the points I make in this blog.

This blog, however, allows me a more impassioned approach. In our increasingly challenged landscape (due to the demands we make of it), there needs to be room for all approaches to conservation management that are evidence-led (e.g. our work at Allerton Trust or the role of grouse moor management) if we are to reverse the decline of nature.

In these cases, conservation values based on science need to trump poorly informed public values based on emotion. Whilst the provision of suitable habitat is a must, in many cases so is the removal of predators during the breeding season. Only in this way will some species be around for future generations. Is that not the definition of sustainable?