By Henrietta Appleton, GWCT Policy Officer (England)

In recent weeks I have been revisiting the known causes of the declines seen in some of our bird species such as the Curlew, Lapwing and House Sparrow and so the recently published paper “Farmland practices are driving bird population decline across Europe” caught my eye. Given the research the GWCT has undertaken since its inception, principally on the causes of declines in grey partridges, it comes as no surprise that the intensification of agricultural production, driven by a policy to increase yields, has had an impact on bird populations.

Connection between agricultural practices, insect declines, and farmland birds

We recently responded to a Commons select committee inquiry on insect declines highlighting that the Sussex Study long term database suggests that agricultural practices are continuing to impact insect numbers, particularly specialist species, despite a levelling off in insecticide use, something known to impact populations. Declines in insect numbers coincide with the declines in birds that feed on invertebrates, either as chicks or adults, which comprise much of our farmland bird cohort.

So given we know that declines in insects are related to the intensification of agriculture and that many farmland birds are insectivorous at some point in their life cycle, it remains a concern that the conservation measures supported by policy have so far failed to address the demise of many of our indigenous species (both insect and bird!). This brings me to the question in my title – have critical thresholds been reached?

The concept of critical thresholds: habitat loss and depensation

The term ‘critical threshold’ is often associated with habitat provision/cover[i] and defines an abrupt change or response in species population levels because of habitat loss or fragmentation. However perhaps more appropriate now is the concept of density-dependent population dynamics and depensation. This is where species population growth rates have become negative as a population is unable to reproduce sufficiently to at least maintain its population and has the potential to accelerate population declines generating local extinctions[ii]. If approaches to conservation, based on habitat alone, have not prevented such thresholds being reached in a variety of bird populations, then surely now is time to call for more action.

One could argue that this point has been reached already due to the increased attraction of conservation models based on species reintroductions or translocations. But why wait for species to reach critical depensation when in many cases the conservation answer is already known? Does conservation not mean saving our species? Studies have found that depensation is connected to increased rates of predation, particularly at lower population densities[iii].

As mentioned above the GWCT has researched the causes of wild grey partridge population declines and through one experiment[iv] on Salisbury Plain, and two demonstration areas - Royston and Arundel - identified the importance of predation management alongside habitat provision in their restoration.

The Allerton Project: a model for supporting farmland birds

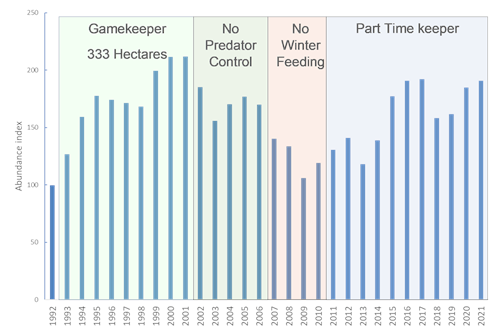

At the Allerton project, the GWCT has demonstrated what needs to be done to support farmland birds alongside a commercial farming enterprise – and this includes protection from predators as well as habitat provision and supplementary feeding. We have not just done this once but twice as the graph below shows. The increases observed in the initial period 1992-2001 and then again in 2010 occurred when we had a wildlife warden operating across the farm. He oversaw the provision of habitat in support of all stages of the lifecycle (brood rearing cover providing insects for the chicks; abundant/quality nesting cover and winter cover and food) with supplementary feeding provided through the hungry gap. In addition, he undertook predation management to protect the hens and chicks during the breeding season from legally controllable predators such as foxes and corvids.

The declines from 2002-2010 coincided with the removal of two legs of the stool – firstly predation management and secondly supplementary feeding. The significance of this is that it demonstrates that the reliance on habitat alone is not sufficient to increase the populations of many of our farmland birds and therefore deliver the wildlife outcomes that Government seeks to achieve biodiversity targets.

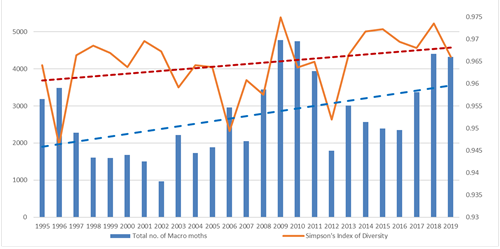

Such ‘active’ management is also benefitting a range of other species such as brown hare[v] and moths (see below). We have monitored moths since 1995 using a Rothamsted light trap as part of the national monitoring network. This network of traps reveals a 33% decline nationally in the abundance of macro-moths between 1968 and 2017. However, at the Allerton Project overall abundance of macro-moths was 36% higher in 2019 than it was in 1995.

Shifting focus to breeding success in policy

If we take the messages from GWCT research and the Allerton project further, rather than overall population levels it is breeding success that policy should be addressing.

This all leads me to worry that by focussing on overall population trends, policy has overlooked the problems that nest failure rates and chick losses store up in terms of a species ability to at least maintain its population level, particularly in the longer life span species. In other words, the decline in our biodiversity so evident in short-lived ‘indicator’ species such as the grey partridge (and insects!) has, for longer-lived species been cushioned at a broader population level by their longer life spans such as those found in waders (maximum ages can be between 20-40 years) and raptors (which can reach 15-20 years of age).

The ‘perfect storm’: habitat loss, predation, and climate change

We have reached a point where the longer-living species are dying off and/or getting beyond breeding age and are facing the consequences of management changes that have affected their reproductive success over a long period. In addition, the impacts of habitat loss and fragmentation and predation are now compounded by the effects of climate change and the migration of climatic envelopes, creating a ‘perfect storm’.

If this is proven to be the case, then the example of Allerton for farmland birds, with its combination of habitat, predation management and supplementary feeding, and grouse moors for upland waders, with the combination of habitat and predation management, in improving breeding success must be acknowledged in policy ambitions if Government targets are to be met.

[ii] Horswill et al (2016) Density dependence and marine bird populations: are wind farm assessments precautionary? JAppEcol 54(5) https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12841

[iv] Tapper, S.C., Potts, G.R., & Brockless, M.H. (1996). The effect of an experimental reduction in predation pressure on the breeding success and population density of grey partridges Perdix perdix. Journal of Applied Ecology, 33: 965-978.); Aebischer, N.J. & Ewald, J.A. (2010). Grey Partridge Perdix perdix in the UK: recovery status, set-aside and shooting. Ibis, 152: 530-542; and,Ewald, J.A., Potts, G.R., & Aebischer, N.J. (2012). Restoration of a wild grey partridge shoot: a major development in the Sussex study, UK. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation, 35: 363-369.

[v] Reynolds, J.C., Stoate, C., Brockless, M.H., Aebischer, N.J., & Tapper, S.C. (2010). The consequences of predator control for brown hares (Lepus europaeus) on UK farmland. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 56: 541-549