By Henrietta Appleton, GWCT Policy Officer (England)

3 minute read

I was struck by a quote from HL Mencken that was used by Baroness Bennett of Manor Castle in a report stage debate on the Genetic Technology Bill(1) – “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong” – as it seemed to me to summarise the problem with a lot of environmental policy at the moment. Policy decisions are seen in binary – right or wrong, ban it or promote it. Yet our ecosystem involves a multitude of interacting processes that result in a dynamic environment.

Policy decisions made on the basis of simple answers from evidence “at a point in time” or over short (3-5 year) time scales are therefore more than likely going to be ineffective or wrong (or both). Consequently, it is not a surprise that on-going research led by Associate Professor Andreas Heinemeyer at York University into upland management systems is beginning to show that the results of earlier research based on pre- and immediately post-burning evidence are too simplified; and even wrong when it comes to judging the carbon consequences of managed burning.

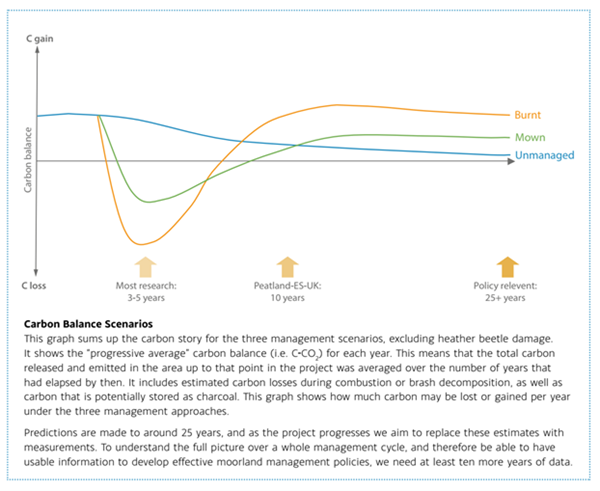

This is because the earlier research failed to acknowledge the processes that takes place over a complete management cycle. Clearly carbon is released at the point of burning but it is reabsorbed over time. This graph from the York University report demonstrates the importance of viewing carbon balances over time:

It also suggests that there is a carbon benefit to burn management over cutting as it demonstrates the additional gain from the charcoal formed during a low-intensity controlled burn. Consequently, the burnt plots become a carbon sink after 5-7 years whereas the mown plots take a bit longer (7-9 years).

The study is also monitoring the effects of management on other ecosystem services – not just carbon. The results to date suggest that the management options of burning and cutting also increase biodiversity, through maintaining structural diversity, and maintain higher water levels compared to the unmanaged sites.

With the increasing threat of weather patterns that are supportive of the devastating wildfires seen at Saddleworth Moor in 2018 and across the country in July 2022, the risk of wildfire must become a significant driver to land management decisions in our semi-natural habitats – and in particular our peatlands. This research reinforces concerns that rewilding or reduced management would increase the wildfire risk as a result of a higher, dry fuel load combined with the effect of the peat drying out as the water table lowers over time due to increased evapotranspiration from the vegetative cover.

Significantly for policy, the experiment is demonstrating that there is “no one size fits all” in terms of upland management and that therefore all available options for land management must remain on the table. In some cases, cutting will be more appropriate (subject perhaps to a wildfire risk assessment on drier sites if the brash is to be left) and in others prescribed burning.

But what is perhaps clear is that leaving huge swathes of our uplands unmanaged provides the poorest possible outcomes. As we stated in our recent audit of grouse moor management’s contribution to 25YEP goals(3) "We find little consistent evidence that the alternative land uses would better integrate, replace or sustain goods and services” and these results do little to change that view.

In the same debate on the Genetic Technology Bill referred to above Lord Krebs when describing the varying views held by scientists in the field of genetics stated that it is usually the case that “scientists do not agree on everything” and that instead one should consider “a centre of gravity of opinion” where science evolves towards a consolidated view. This is also the case with peatland ecology and its interaction with fire ecology.

But interestingly Lord Krebs went on to say [with regard to genetics and gene-editing] “.. when there is a centre of gravity of opinion, there are always outliers. Sometimes those outliers turn out to be right and there are transformations, but I have seen no evidence at this stage that the outliers are right and the centre of gravity is about to shift”.

This is also relevant here as Associate Professor Andreas Heinemeyer has been seen as an ‘outlier’; yet surely the results of his 10-year experiment (with another 10 years to come) are the evidence needed in peatland ecology and its interaction with surface vegetation and fire ecology that this should be a transformational moment.

References

1. https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2023-01-25/debates/6D8A0914-F879-4480-B78F-8BBD8F4CE3E6/GeneticTechnology(PrecisionBreeding)Bill

2. Heinemeyer, A. (2023) Protecting our peatlands. A summary of ten years studying moorland management as part of Peatland-ES-UK: heather burning compared to mowing or uncut approaches. Full report can be found here.

3. Sustaining ecosystems - English Grouse Moors (GWCT)