We have recently published Conserving Our Woodcock, a new guide which turns 50 years of GWCT woodcock research into practical guidance on how to provide the varied habitat woodcock require. This blog is taken from the guide, which you can download in full here.

The woodcock is a cryptic, beautiful, and interesting bird. Characterised by its mottled brown, black, and grey colour, stocky shape, short legs, and sizeably long bill, it is an expert in camouflage. It is relatively unknown in many quarters, perhaps because its life is not lived in plain sight – it is most active at dawn and dusk and is generally averse to disturbance. It breeds in rural woodlands, feeding by night on open ground including pasture and arable farmland, so although it is much loved by some people it is rarely seen by most.

Despite this, the woodcock played a surprisingly large role in the early days of British ornithology. As early as the 1890s, monogrammed rings were fitted to the legs of woodcock chicks at country estates across Scotland, Ireland, and northern England. The recoveries of these ringed woodcock during the shooting season were among the first real opportunities to understand the movements of wild birds. Woodcock became the subject of these early ‘citizen science’ endeavours because they were, and still are, a much-loved quarry species that has earned a prominent place in country lore.

To this day, there are still many unanswered questions about this mysterious species but 50 years of woodcock research, conducted by the GWCT, means that we now have a better understanding of the woodcock’s ecology than ever before. Over the last decade, new technology has revolutionised the way in which we study birds and has provided never-before-seen insights into the species’ migration and breeding behaviour.

These studies have revealed the epic journeys made by migratory woodcock that spend their winters in the British Isles, as well as highlighting the plight of our small resident breeding population. They have also helped us to better understand woodcock habitat requirements so that we can work to ensure we support their needs.

This document tells the story of GWCT’s woodcock research and how our improving understanding of the species can help inform future attempts to conserve woodcock in Britain and Ireland.

Woodcock Worldwide

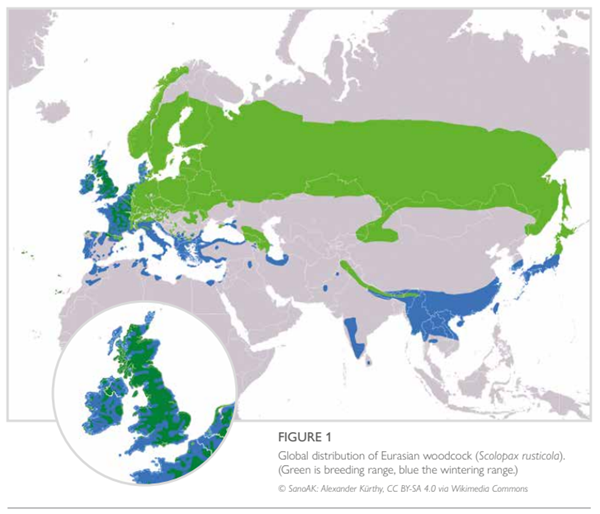

Woodcock are found in woodland habitats right across northern Europe and Asia, ranging from Britain in the West to Japan in the East.

Information on the size of breeding woodcock populations worldwide is relatively poor and the accuracy of estimates varies from country to country. By far the largest numbers, however, are known to breed in the expansive northern forests of the Baltic States, central Europe, Finland, Scandinavia, and Russia.

Owing to their diet of invertebrates and the manner in which they probe the ground with their bills to find food, woodcock are unable to feed when the ground is frozen. Birds from these northern and eastern populations must therefore travel south and west to escape the winter freeze on their breeding sites.

Between December and March, the bulk of the European population is concentrated in Britain, Ireland, France, Spain, Italy, and Greece, where conditions are comparatively mild. We estimate that between 800,000 and 1,500,000 woodcock overwinter in Britain and Ireland.

At a global scale, woodcock are classified as being of least concern by the IUCN because of their large, relatively stable population and large range.

The best estimate of their global population from the 2021 European Red List is put at 11.5 million individuals and they are widespread across their breeding and wintering ranges (FIG 1).

The conclusion that the global population is of least concern is based largely on numbers for the largest population in Russia, although there are some more localised populations for which trends are either unknown or declining, such as UK breeders. Woodcock monitoring in the main European breeding areas (in Scandinavia and Russia) indicates that the European population is stable, and there is no evidence for a change in the numbers of migrant woodcock wintering in Britain and Ireland.