By Henrietta Appleton, GWCT Policy Officer (England)

4 minute read

The war in Ukraine has added to the pressures farmers are facing through increasing input costs of the three F’s; fuel, feed and fertiliser. These could be short-term impacts but they come at a time when the industry is facing longer-term upheaval due to reductions in post-Brexit farm support, labour shortages and the impacts of trade and environmental policies.

The combined effect of these factors is of concern if it has an impact on domestic food production. The globalisation of our diet and the increasing distance between our food demands and our ability to meet these domestically means that our food supply is likely to increasingly rely on imports (UK imports comprised 46% of the food consumed in 2020 ). Consequently, we need to consider the level of domestic self-sufficiency we have in temperate food production.

However, the political focus at the moment is on the cost of living crisis. What many politicians are missing is that this will only intensify if our domestic food security is undermined. We explain why this threat is very real.

According to data analysed by Anglia Farmers, the rate of agricultural input inflation has hit 46% in the past 18 months, with the market price of nitrogen fertiliser quadrupling between summer 2021 and February 2022 to £1000/tonne. Similarly, the price of red diesel doubled in a similar time frame, while the costs of some key plant protection products have increased by similar amounts.

Although forward buying and the increase in arable commodity prices may have cushioned the impact for some in the combinable crops sector for harvest 2022, there are genuine concerns over the impact of these price rises for the cropping campaign beginning this autumn, and even over the availability of fertiliser, with global stocks stretched and domestic production severely limited. Based on current input prices, fertiliser use is likely to decline which is likely to result in lower yields (although the extent of this will be dependent on a number of other factors too such as quality of land, previous cropping etc).

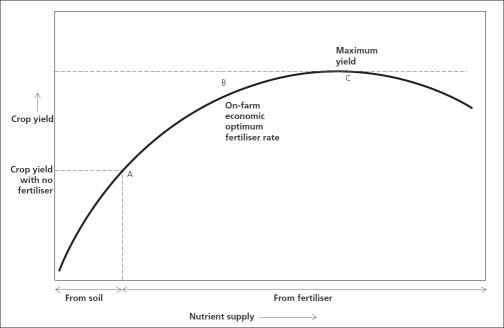

What we need therefore is to support our farmers in improving their resource use efficiency - and also to consider alternative sources of nitrogen. Improving nitrogen use efficiency (see graph) will have beneficial environmental impacts too such as reducing losses from the system and reducing inorganic N use (with its associated carbon footprint) - one of the few potential long-term win-wins from this situation.

The high price of natural gas is also driving fertiliser manufacturers to look at alternative sources of hydrogen to make ammonium nitrate, for instance by using solar, hydro or wind generated electricity to electrolyse water. However such developments will not be able to significantly impact production models in the short term, and government must work with industry to mitigate the impact of an immediate shortage of this vital resource, which is central to our ability to produce plentiful, quality food.

Livestock farmers face similar problems around the availability and cost of nitrogen fertilisers to produce forage for their animals, but are also facing significant feed cost increases as higher commodity prices pass down through the supply chain. This is causing significant pressure on margins, especially in the dairy, poultry and pig sectors. In the last six months, we have already lost some 10% of the national pig herd as the sector contracts due to chronic labour shortages, paired with cost increases.

Horticultural production in the UK is set to shrink by some 25% this year, as growers decline to plant loss-making crops, coupled with the departure of the Ukrainian workforce and competition from imports produced under looser environmental regimes facilitated by recent trade deals. The cost of energy is also severely impacting those sectors with a high requirement, such as housed poultry and indoor horticulture.

Given these challenges and the broader policy background of the Agricultural Transition to the Environmental Land Management Scheme and associated uncertainties, the need for land to support offsetting (be that carbon or biodiversity) and alternative energy sources such as solar and bioenergy, many farmers will be considering whether the uncertainties of food production are worth facing.

Income from alternative land uses/managements effectively de-risks farm businesses from input shortages - and the weather. Consequently, we are already seeing significant areas of land taken out of production (often put into Countryside Stewardship), lower numbers of livestock taken forward, and a focus on lower-risk, lower yielding crops such as feed and spring wheats over milling wheats, used for bread production. The National Farmers Union has warned that the UK faces the risk of a double-digit decrease in domestic production as a result of the challenges it currently faces.

Government recently acknowledged that food security is a public good (UK Food Security debate 26th April 2022) but with more land likely to be taken out of production or put into more extensive production to support biodiversity and area-based conservation ambitions, a distinction should be made between domestic self-sufficiency and food security. Otherwise we may find our abilities to continue our self-sufficiency of around 75% in crops that can be commercially grown in the UK (a figure that has remained stable over the last two decades)1 an increasing challenge.

Given the recent evidence of the fragility of our food system evidenced by Covid-19, Brexit and the war in Ukraine, this would likely be an unwise trajectory to follow, before we begin to account for the lower environmental and climate impact of British production versus global averages.