Written by Phil Warren for Gamewise Magazine. Photos provided by Sarah Grondowski.

3 Minute Read

Black grouse in the UK have declined severely in both numbers and range over the past 150 years. The last national survey in 2005 estimated 5,078 males, 3,344 in Scotland, 1,521 in northern England and 213 in north Wales. In 1996, following the first UK Birds of Conservation Concern assessment, they were identified as one of 36 species of high conservation concern and ‘Red Listed’. Some 25 years later, following the recent Birds of Conservation Concern 5 assessment they remain on the Red List. This is due to a historical population decline, with numbers declining by 22% between national surveys in 1995/6 and 2005 and by 36% between 1995/6 and 2019.

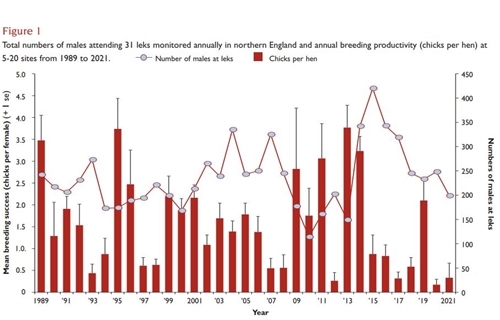

To measure trends in numbers over time in northern England we count the numbers of lekking males at 31 sample leks annually since 1989, and measure annual breeding success at five to 20 black grouse specific count sites using pointing dogs.

Since 2015, there has been an unprecedented run of six poor breeding years in the past seven, with annual breeding productivity in these years ranging from 0.2 to 0.8 chicks per female (see Figure 1). This is less than the 1.3 chicks per female required to maintain stable numbers in northern England. Over this period, the predicted June chick hatch has been during four of the wettest Junes in the past 30 years. Such wet or cold June weather is linked to poor chick survival caused through direct chilling of chicks and there being few active insects for them to eat. Hitherto, chick survival has often been better when June has been drier, but during two recent dry Junes, including 2018 the driest on record, birds have still bred poorly.

This run of poor breeding years has led to a 53% fall in the numbers of males attending leks since spring 2015 (see Figure 1). Given further poor breeding (0.3 chicks per female) last year, we predict a further drop in birds at leks next spring. Despite this, the overall 33-year trend at these leks remains stable, indicating that the population in northern England has been sufficiently large to withstand these set-backs of poor breeding years. However, if patterns of poor breeding become normal, then further declines, local extinctions and range fragmentation will become increasingly likely.

The decline at leks in northern England since 2015, has also occurred across much of Scotland. Males at Perthshire and Deeside leks (north-east Scotland) and those in the Beauly Catchment (north Scotland) have seen similar declines since 2015 of 42%, 46% and 36% respectively. Here, in northern England, the longer-term trend (2005-2021) remains stable, again suggesting that larger contiguous populations as found in northern England (c.1,500 males in 2005), north (c.800 males) and north-east Scotland (c.1,500 males) can withstand these periods of poor breeding. In contrast, the impacts of this run of poor breeding years on smaller populations in Dumfries and Galloway and the southern uplands, both in southern Scotland, is of concern. Here, numbers have declined by an estimated 7% and 10% per annum since 2005 and are now approaching a critically low level (200 males across the whole of southern Scotland) whereby remaining lekking groups are small, and could become isolated with little chance of recovery.

Extreme weather events as part of progressive climate change are predicted to become more frequent and could continue to impair breeding success. To help buffer against possible continued lower levels of breeding success into the future, survival of adult birds needs to be maximised by controlling their predators such as foxes and stoats and marking or removing often fatal hazards of wires and fences. In the longer-term, the retention of large contiguous areas of habitat capable of supporting several lekking groups needs to be ensured. Finally, we need to address the question whether improving the management of habitats used by chicks to support more insects such as moth and sawfly caterpillars, can be achieved to provide a positive trade-off against inclement June weather.

Research in action... How to survey Black Grouse

1. We monitor Black Grouse numbers by counting the numbers of males attending leks in April and May. We search for lekking males suitable vantage points between dawn and 7am.

2. We survey annual breeding success by searching favoured habitats with trained pointing dogs in August. The dogs scent black grouse allowing us to count any young present.