The practice of controlled heather burning1 has come under increasing scrutiny given the focus on achieving Net Zero ambitions through reducing carbon emissions from peatlands. Whilst the effectiveness of limiting controlled burning in pursuit of these objectives is still debated (see for example Carbon storage on grouse moors), the unintended consequence of this focus is to present heather as the villain.

As the Trust highlights in a recently published audit of Grouse Moor Management2, “Current approaches to net zero…[emphasise] reducing heather as part of peatland restoration (by wetting and reducing burning) and enhancing woodland cover”.

Whilst this blog will focus on upland heather moorland, there are important areas of lowland heath, not least the New Forest where the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT) has its HQ. Lowland heath is also in decline with, according to the JNCC, only about one sixth of the heathland present in 1800 remaining. In addition to land use change, both habitats are likely to suffer from the changes in climate we are experiencing.

Estimates suggest that upland heather in England & Wales had already declined by 27% between 1945 and 19803. But the Trust’s audit revealed that there is no consistent measure of upland heather extent in England so it is difficult to gauge the trend. Since 2015 on CEH land cover maps heather has been mapped in two categories: heather and heather grassland. However, the long-term monitoring data (1990 to 2015) did not distinguish between these categories. Despite this uncertainty, recent data suggests the trend continues.

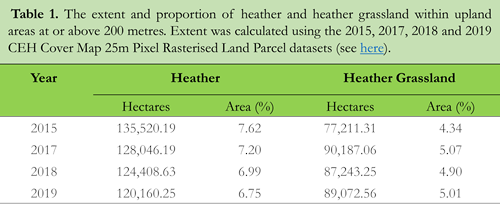

CEH defines the ‘Heather’ habitat category as areas where there is greater than 25% heather cover3 and ‘Heather Grassland’ as areas where heather cover is less than 25%. The need to create this distinction in itself could suggest a decline in quality, if not extent, as the UK’s first Convention on Biological Diversity national report in 1998 referred to less than 50% dominance4. However, the data for these categories since 2015 (see Table 1) shows a continuing decline in heather (11% reduction in area over the four-year period), balanced to some degree by an increase in heather grassland although there is still a 2% overall decrease between 2015 and 2019.

In Scotland upland heath was estimated to cover approximately 778,000ha in 2008. Its extent was impacted by the expansion of plantation forestry, supported by government subsidy, from the 1940s to the late 1980s. Between 1990 and 2007 there were no significant changes in extent but there was a notable decline in species richness5.

These trends are a concern. Defra, Natural England and NatureScot (and other advisory bodies and eNGOs) must not forget that heather habitats are internationally protected (the value of this habitat was ratified by the 1992 Rio Convention on Biodiversity) and must continue to regard them as a priority for conservation. Although the claim that the UK has 75% of the world’s heather moorland is unsubstantiated (see What the Science says review of 75% figure) the UK is custodian to a significant majority of its extent (between 2 and 3 million ha6); and the fact that the true figure of its presence here is unknown is of concern.

Given that the focus on climate mitigation (and to some extent other public goods such as flood mitigation) is amplifying this loss by focussing on peat restoration, it is important that the value of our upland heather to public good provision is reiterated before policy becomes too blind to it.

Let us begin by reviewing its value to our plants and wildlife. Upland heathland is defined by its vegetation and is found on a mixture of drier deep peats or on wet, acidic, impoverished, shallow organic soils. It does not just consist of heather, specifically Calluna vulgaris; it is a mosaic of dwarf shrubs, grasses and mosses.

It encompasses a range of National Vegetation Classification plant communities broadly relating to Wet and Dry Heath assemblages including bilberry, crowberry, gorse (in the south and west on the drier heath), juniper (largely in Scotland), cross-leaved heath, deer grass, cotton grass and purple moor-grass as well as an understory of mosses including the ‘magic’ Sphagnum. The seminal paper on upland heather moorland by Thompson et al in 19957 reviewed the international significance of this sub-montane habitat.

The paper records 19 constituent plant communities, 11 of which are significantly represented by or largely confined to GB, and a bird assemblage of 40 species including curlew, black grouse, ring ouzel, twite, merlin, short-eared owl, red grouse, golden plover, meadow pipit and hen harrier. Heather also supports important invertebrates and significant lepidoptera biomass; for example, it can support more beetles than grass-dominated habitats – an important consideration if heather grassland is a sign of conversion to grass.

Given that birds are often seen as indicators of the health of an ecosystem/habitat it is no coincidence that the loss of heather habitats has also harmed upland bird populations. In the Welsh uplands serious declines in waders and other upland bird species have accompanied the loss of 50-75% of heather since 19458. In Scotland the mountain hare is strongly associated with heather moorland managed for red grouse shooting due to beneficial heather habitat management and predator control carried out by gamekeepers9.

Whilst the biodiversity value of heather is generally accepted, it is arguably the delivery of other public goods that is currently driving upland policy: namely, carbon and flood mitigation. What value heather to these? As the recent Natural England assessment of Carbon Storage and Sequestration by Habitat10 stated: “Heathlands store significant carbon stocks, mostly in their soils, comparable to that of peatlands in the top 15 cm” with estimates putting this at c95t of C/ha (range 88-103).

Wet heaths however contain greater soil C stocks than dry heaths. This does not include the C store within the vegetation (estimated at c6 t C/ha (range 2-9) – nor that of the litter carbon pool. Whilst extensive data does not exist for upland grasslands, the soil C estimates are generally less than for heathland (wet heath in particular) and there is evidence from both Scotland and northern England that the transition to grassland due to heavy grazing or reduced burning management reduces carbon sequestration and the carbon stock within the vegetation and top 15cm of soil11.

Heathland can also sequester double the CO2 of grass-dominated vegetation. Consequently it has been suggested that restoring upland heathland on mineral soils could increase sequestration comparable to that of woodland over the timescale required for the UK to achieve net zero i.e. by 205012 (as well as improving biodiversity). As regards flood mitigation, research has shown that the surface ‘roughness’ presented by the vegetation is an important controlling factor whilst canopy interception might account for almost 50% of rainfall13 thereby ‘controlling’ its onward passage to the ground.

So given this evidence, when focusing on peatland restoration, it is important that heather is not demonized to the extent that its own restoration over succession to scrub, woodland or grassland is ignored.

References

- Controlled heather burning here is that which is undertaken in accordance with the code of practice and recent controls on burning on deep peat.

- Sustaining ecosystems – English Grouse Moors.

- This ties in with the definition of Heathland vegetation as occuring widely on mineral soils and thin peats (<0.5m deep) throughout the uplands and moorlands of the UK and characterised by the presence of dwarf shrubs at a cover of at least 25%.

- “Upland heath … occurs on some 3.7 million ha of land, though, of this 1.6 million ha have less than 50% heather dominance.” https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/gb/gb-nr-01-en.pdf

- Sustaining Scotland’s Moorland: The role of sporting management in sustaining our upland ecosystems https://www.gwct.org.uk/media/550372/Sustaining-Scotlands-moorland.pdf

- BRIG (ed. Ant Maddock) 2008 UK Biodiversity Action Plan: Priority Habitat Descriptions.(Updated 2011)

- Thompson, DBA et al (1995) Upland heather moorland in Great Britain: A review of international importance, vegetation change and some objectives for nature conservation, Biological Conservation, Vol 71 (2) https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(94)00043-P.

- https://www.gwct.org.uk/media/763714/BMBMR-Nature-Fund-Upland-Recovery-Project-NF-CG-002-30-10-15.pdf

- Stoddart, D. & Hewson, Raymond. (2009). Mountain hare, Lepus timidus, bags and moor management. Journal of Zoology - J ZOOL. 204. 563-565. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1984.tb02388.x.

- Gregg, R et al (2021) Carbon storage and sequestration by habitat: a review of the evidence (second edition) Natural England Research Report NERR094. Natural England, York.

- Baggaley NJ, Britton AJ, Barnes, A, Buckingham S, Holland JP, Lilly A, Pakeman RJ, Rees RM, Taylor A, Yeluripati J. 2021. Understanding carbon sequestration in upland habitats. ClimateXchange. http://dx.doi.org/10.7488/era/1021

- Friggens, N.L., Hester, A.J., Mitchell, R.J., et al. 2020.Tree planting in organic soils does not result in net carbon sequestration on decadal timescales. Global Change Biology, 26: 5178–5188]

- Stoof, CR et al (2012) Hydrological response of a small catchment burned by experimental fire Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 16, 267–285 doi:10.5194/hess-16-267-2012