We have recently published Conserving Our Woodcock, a new guide which turns 50 years of GWCT woodcock research into practical guidance on how to provide the varied habitat woodcock require. This blog is taken from the guide, which you can download in full here.

The GWCT has been carrying out woodcock research since the 1970s, with a programme of studies that has only intensified as it has progressed through the decades, each building on those that have gone before so that a more detailed picture has developed. This complex species provides many avenues to study, and the relative scarcity of robust information that came before means that our understanding of both breeding and migratory woodcock has grown enormously along with this body of work.

GWCT research has focused on two main areas:

1) Breeding ecology, and 2) Migration research and winter ecology.

This document offers a summary of the research to date focused on our breeding woodcock. The GWCT is committed to improving our knowledge of the species and helping support its conservation. A full report on the findings of our research on woodcock migration and population status carried out alongside the studies reported here will follow in 2024.

The early days: woodcock breeding studies

In the 1970s and 1980s, early projects used radio transmitters to better understand the male woodcock’s roding flight. Birds were caught at night and radio transmitters attached to their backs. They were then monitored by a team of researchers spread throughout the wood with hand-held radio receivers as well as static receivers on trees or poles.

This project was the first of its kind and discovered that:

- Woodcock roding is not for the purpose of maintaining an exclusive territory, as had previously been accepted, but is instead for locating and attracting females

- Roding ranges overlap considerably, with areas shared by multiple males

- Once mated, males stay with a female for several days until egg-laying begins. They then return to roding and some males may mate with further females through the season

- This lack of exclusive territories, variation in the amount of roding by individual males, difficulty in distinguishing individual birds, and finding that males sometimes rode over a number of separate woodlands meant that previous population estimates were unlikely to have been reliable, and it informed the development of the new techniques for population estimation that we use today

- The estimated size of roding ranges, according to the technology of the time, was between 43 and 134 hectares (an average of 88), or around 0.9 square kilometres.

Continued radio-tracking and nest-finding in the early 1990s showed that females typically nested in more open woodland stands with dog’s mercury, bluebells, or sparse bramble cover in a lowland study area. In an upland study area, they favoured mature birch woodland with a bracken or grass field layer.

When feeding, adult woodcock frequented areas of denser, younger trees at both sites and broods were also taken to these areas. The use of dense, younger trees or stands with a good shrub layer is thought to be related to avian predation risk, as both sparrowhawks and tawny owls predated woodcock at these study sites.

Sonogram studies: solving the mystery

Prior to this landmark work, it had been impossible to identify the number of woodcock in a particular area during a survey because the surveyor cannot tell individual birds apart by observation. When surveying, each roding flypast is called a ‘registration’.

In a single evening, it may be possible to record 20 or 30 registrations at a good site, but as the birds are not identifiable, it is not possible to know whether these are performed by one active male or several different males.

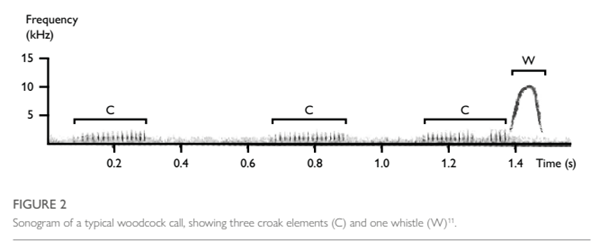

To address this, the GWCT undertook studies in the early 2000s which used sonograms to record and identify individual woodcock from the characteristic calls that they make during roding flights in the breeding season (FIGURE 2).

The researchers recorded calls made by different woodcock, measured the minute differences in specific characteristics of each call, and demonstrated that these measures allowed most individuals to be distinguished.

This was critical to assessing woodcock numbers and allowed us to calculate how the number of woodcock ‘registrations’ relates to the number of woodcock that would likely be present in the area at that time. For instance, a survey with 4-6 registrations would equate to 2-3 individual roding males whereas a survey yielding 18-20 registrations would suggest that 6 separate males were displaying.

National surveys and numbers

The first national survey of breeding woodcock in Britain took place in 2003. Surveys were carried out in conjunction with volunteers from the British Trust for Ornithology. Volunteers counted woodcock at over 800 1km squares throughout Britain. The sample of squares was randomly selected, in a way that accounts for variation between regions and different woodland coverage. These sites were each surveyed three times between May and June for an hour, starting from 15 minutes before sunset.

The information from these surveys was collected and analysed using the method developed from the sonogram studies described above, to give an estimated breeding population in Britain of 78,346 males. Our method also provides a ‘confidence interval’, the likely window either side of the estimate that the true value is thought to lie within. This suggests that we can be 95% sure the population was between 61,717 and 96,493 males. This estimate was much higher than previous ones made between the 1970s and 2006, but was still thought likely to be lower than the real number.

In 2013, the national survey was repeated to give two important pieces of information – the second national population estimate using these techniques, and the first opportunity to compare from the 2003 baseline figure. This work gave a population estimate of 55,241 males (the 95% confidence interval around this figure is 41,806 to 69,004 males) and suggested that the population had fallen by almost a third in ten years, a finding that fits with data from general bird monitoring schemes. The next national survey will take place in 2023.