By Mike Short, GWCT Head of Predation Research

6 minute read

According to the Curlew Recovery Partnership, around two thirds of all curlew pairs breeding in the English lowlands occupy agricultural grassland habitats affected by seasonal grass-cutting. Clearly, this presents a major hazard to ground-nesting birds, with vulnerable nests and chicks hiding in hay and silage crops exposed to the whirring blades of mechanical mowers.

According to the Curlew Recovery Partnership, around two thirds of all curlew pairs breeding in the English lowlands occupy agricultural grassland habitats affected by seasonal grass-cutting. Clearly, this presents a major hazard to ground-nesting birds, with vulnerable nests and chicks hiding in hay and silage crops exposed to the whirring blades of mechanical mowers.

In comparison, the curlew that return from the coast to breed on the open heaths and wet valley mires of the New Forest each spring are relatively lucky. There are no speeding tractors or flailing mowers here; this is an ancient semi-natural landscape with top-level wildlife protection. The New Forest is classified as a Special Protection Area for its breeding and overwintering birds; a Special Area of Conservation for its unique and diverse habitats; a Ramsar site, which recognises it as a wetland area of international importance; and 29,000 hectares of the New Forest are designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in recognition of its outstanding ecological and geological importance.

So, with multiple layers of conservation ‘protection’ in place, why is it that the New Forest’s breeding curlew population is in such dire straits? Well, basically, it’s because every year, most curlew breeding attempts end in failure, and as a result, this population is failing to replenish itself. Unless this tragic situation changes very soon, then the soothing sound of curlew bubbling over the Forest’s heaths, is likely to become but a distant memory.

Building on previous New Forest breeding wader studies conducted by Hampshire Ornithological Society and Wild New Forest, the GWCT’s curlew work here began in 2020 as a PhD project jointly funded by Bournemouth University in collaboration with Forestry England, and since that time, our program of breeding wader and predation research in the Forest has grown considerably. Our intention is to use the power of science to help drive a strategic and focussed wildlife management plan aimed at recovering this increasingly fragile population of curlew.

In 2020, close monitoring of 40-45 curlew pairs revealed very high nest losses with approximately two thirds of 31 observed nesting attempts failing, and only 3 chicks surviving until fledging age. To maintain a stable population, each curlew pair must fledge approximately 0.5 chicks/pair per annum, so they fell well short of that.

Understanding the root cause of nest failure is paramount to knowing which predators to target with management, so in 2021, we used trail cameras to monitor curlew nests. From late April until July, we found 18 active nests; other fresh nest-cups were located too, but by the time we’d discovered them, the eggs were lost, presumably to predators. Of the 18 nests monitored with cameras, 14 were predated, mainly by foxes and carrion crows.

This trail camera image shows an incubating curlew leaving its nest

This trail camera image shows an incubating curlew leaving its nest

A carrion crow arrives and predates the eggs

A carrion crow arrives and predates the eggs

… and it seen eating a soon-to-hatch curlew chick

In 2021, on one Forest area important for breeding curlew, the new wildlife manager responsible for the beat carried out intensive fox and carrion crow control during the nesting season, and six curlew chicks fledged from his beat alone: so more than twice the number of chicks that fledged from the entire New Forest area in 2020.

This year, we will repeat our nest monitoring work, and the first nugget of ‘green gold’ – a fresh curlew egg – was discovered over the Easter Bank Holiday weekend. From now until mid-July, we will spend many hours searching for curlew nests across the New Forest, and this year my colleague, PhD candidate Elli Rivers, hopes to radio-tag a sample of day-old curlew chicks to determine their fate. We know from observing the behaviour of adult curlew, that chicks are typically rapidly lost, and it maybe that we discover different predatory species are more problematic for chicks.

The New Forest is a popular tourist destination, and the National Park Authority in conjunction with Forestry England, runs a seasonal campaign to highlight the plight of ground-nesting birds. Minimising human activity around sensitive breeding areas is important to reduce disturbance; when incubating birds are flushed from their nests, clutches of eggs are left exposed, potentially making them more vulnerable to avian nest robbers like carrion crows.

Their visitor education program is first-class: news and social-media outreach campaigns, strategically located ‘please do not disturb the birds’ signs, and teams of rangers out on the ground, talking to visitors about the importance of keeping to the main tracks and pathways, and keeping dogs under close control. These messages are important and will surely help some ground-nesting birds to breed more successfully, but unfortunately recreational management alone will not prevent foxes from destroying the nests of curlew at night.

This trail camera image shows another curlew incubating her eggs

This trail camera image shows another curlew incubating her eggs

Later that night, a fox arrives and takes all the eggs

Humans can be a wasteful and careless bunch, and opportunistic predatory species like foxes and carrion crows thrive in human-dominated landscapes, for there are usually rich food-pickings to be had. Foxes are not obligate carnivores – that is, they are not reliant on live-prey or meat like cats are: hence, the ubiquitous urban fox, which survives largely on trash. Although we have no firm figures yet, it’s already clear from eyeballing predator activity monitoring and management data, that densities of foxes and carrion crows in the New Forest are particularly high.

There’s a good reason why good places to see carrion crows in the New Forest are around laybys, car parks and campsites: it’s because too many people leave picnic scraps and food waste behind. And from our fox dietary studies, we now know that foxes living around important curlew breeding areas in the New Forest also benefit from human activities. Analysis of stomach contents from foxes culled during the 2021 curlew nesting season shows human waste, like sandwiches, pizzas, pasta, and other food scraps, as well as pet food, to be particularly prevalent in their diet, and anthropogenic foods like these, represented by far the most important fox food category. Of course, there are many other ways in which human activities may benefit and bolster generalist predator numbers - such as by releasing gamebirds - but interestingly we found no gamebird remains in our sample of fox stomachs.

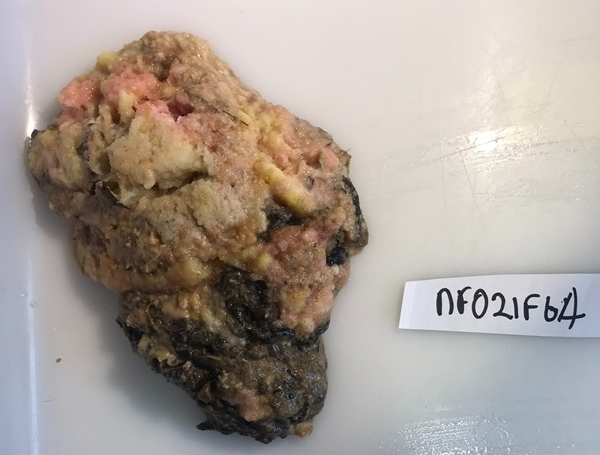

Analysis of fox stomach contents shows that, in the New Forest, human-derived foods provide an important resource. This fox had consumed cat food, cooked chicken, an egg carton label, and larvae

Analysis of fox stomach contents shows that, in the New Forest, human-derived foods provide an important resource. This fox had consumed cat food, cooked chicken, an egg carton label, and larvae

…whilst this fox stomach was full of fish pie.

Until such time that humanity can clean up its act and stop resourcing generalist predators like foxes and carrion crows, then vulnerable species like our beloved curlew will bear the brunt of our ways. There are many other potential predators of curlew eggs and chicks in the New Forest, and it is quite plausible that effective control of fox and carrion crow numbers may result in compensatory predation by protected species, like badger, raven, and gulls.

Whatever the future holds, if we wish to see curlew continuing to breed in the New Forest and elsewhere, then it is critically important that professional wildlife managers are allowed, resourced, and encouraged to get on with their jobs. It’s the only hope that the UK’s breeding curlew population has.