Fox scats are unlocking the secrets of foxes and shedding light on densities, revealing the real pressure on our ground-nesting birds. Mike Short explains...

Wildlife biologists can learn a lot by studying fox poo or ‘scats’ as we call them. As we continue processing the 800 or so samples collected during our recent EU LIFE Waders for Real project, we further unravel the lives of foxes that threaten the Avon Valley’s breeding lapwing and redshank population.

In monetary terms, fox scats are worthless, but to scientists trying to fathom why and how common generalist predators like foxes can have such a detrimental impact on ground-nesting birds, this sample is like veritable gold dust. Unfortunately, our LIFE-funding is over now, but the scats we amassed during the project represent hundreds of hours of fieldwork and a precious resource that we would like to make full use of.

Currently, our Predation lab is a fox scat processing factory. We still have 300 or so samples stored in the freezer ready for analysis, but others are oven-drying so we can weigh them and measure their volume, and others are flaking apart in water. Fox scat ‘soup’ makes the lab whiff, but it’s bearable and all samples are judiciously teased apart.

By estimating the relative proportions of undigested macroscopic prey-items, such as feathers and bird feet, small mammal bones, and fur and teeth from rabbits and hares, we can determine the composition of fox diet and the frequency that various prey-items occur between sites. Alongside natural prey resources which occur locally, foxes are adept at subsidising their diet by exploiting a wide-range of anthropogenic resources, some of which are easily digested and don’t appear in scats.

Scats are oven-dried so we can calculate the dry-volume of undigested prey remains.

For example, we analysed the stomach contents of a fox killed by a valley gamekeeper and found wax-paper wrappings from a McDonalds meal – a clear indication that foxes with access to river meadows can benefit from human food-waste from further afield. The fox population has access to a wide variety of resources on a very large scale, as suggested by an adult vixen GPStagged in the Avon Valley, who travelled to Southampton and back in one night before she was culled on what is arguably the most important wader breeding area.

But a scat can tell us much more than what the fox ate: it also reveals the fox’s individual identity. From DNA, we can determine its sex, and degree of ‘relatedness’ to other foxes sharing the same landscape. Knowing the number of individuals present, provides important ancillary data to consider alongside our GPS-tracking data.

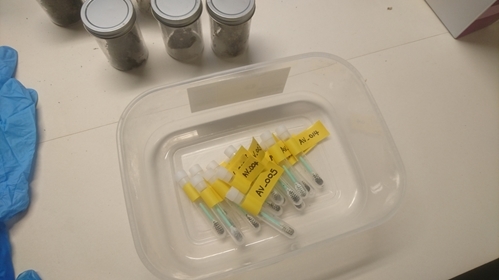

So, before we dissect a scat for diet analysis, we collect faecal DNA by carefully rubbing the exterior surface with a fabric-coated swab. Meticulous care is taken to ensure no cross-contamination occurs. Swabs are stored frozen ready to be shipped to a specialist laboratory, where geneticists use a combination of laboratory and software techniques to distinguish individual identities (genotypes) and determine whether each was either male or female. It costs about £45 to genotype a scat, but it is money well spent. Using the LIFE-funding, we sent DNAyielding material from tagged-foxes and faecal swabs to a Swedish laboratory highly experienced in fox work. The results from this initial sub-sample of scats were, quite simply, astonishing.

The DNA swabs will distinguish individual identities and sex.

In 2017, we GPS-tagged 10 foxes in the Upper Avon Valley on river meadows just south of Salisbury. These 10 foxes occupied two neighbouring fox territories (size = 32 hectares (ha) and 44ha) indicating a density of 13 tagged adult foxes/per 100 hectares which is far higher than we expected. However, genotyping of fox scats gathered between March-May, detected the presence of a further 15 foxes using the same 76ha area. Because of the timings of scat collection, these are assumed to be adult.

Many foxes (both tagged and untagged) were detected from only one scat, so these genotype detections cannot be used to distinguish territory-holding residents from encroaching neighbours or transients that may have been passing through. Nevertheless, it shows the extreme pressure that wading birds are subjected to and may explain why they no longer breed in this part of the valley. In the same project, we went on to GPS-tag foxes in the lower Avon Valley, on river meadows just north of Ringwood.

Lapwing and redshank still breed here, and again, we collected lots of fox scats. Now that we have tasted the power of DNA analysis, we would like to genotype these scats too, to determine whether these birds were under similar fox pressure. This is a potentially revelatory piece of work, perhaps explaining why wader productivity is so poor. Regrettably, the funding provided by our LIFE project would not stretch to that, so unless we can find sponsors – public or private – to fund completion of this ground-breaking research, it will regrettably remain unfinished.