By Joe Stanley, Head of Training and Partnerships at the Allerton Project

This article first appeared in Countryside magazine

5 minute read

Many farmers only ever experience the privilege of farming in a single place. Roots go down, families are raised, immutable connections forged. From infancy to expiry, entire lives are lived within the familiar boundaries of ‘the farm’, often referred to in its own right and as if none others exist. For many years, I thought that this too was my destiny, but in recent months I have found myself a new home in our great countryside – the Allerton Project on the Leicestershire/Rutland border at the delightful village of Loddington.

The Allerton Project is 320 hectares of rolling mixed farmland, a combination of permanent pasture and arable spread astride the Eye Brook stream, a tributary of the River Welland. The village itself consists of a mere handful of sandstone-built houses, straw-sculpted chickens, wheelbarrows and geese adorning the apex of the thatched roofs. The roads in and out are single track and thickly overhung with oak and beech, and given that the village is more of a destination than a route to elsewhere, passing traffic is blissfully scarce.

Loddington can trace its ancestry back to at least the time of Domesday in 1087, by which time it was an already established settlement. The village church – now standing in splendid isolation amid grassy fields of ridge and furrow – can be dated back to the twelfth century, with significant additions in the thirteenth and fourteenth, and is deceptively grand for a hamlet the size of modern Loddington. At one time, the entire manor was held by the Augustinians based at nearby Launde abbey; after the reformation it was briefly owned by Henry VIII’s ill-fated chief minister, Thomas Cromwell. During the Second World War, the sixteenth century Loddington Hall was requisitioned by the army (and suffered as a result) but today still stands as a private home.

To me, my new home at Loddington seems an oasis of calm in an increasingly frenetic world, one of those countless small corners of Britain where to stand and listen to the sound of birdcall in the sun-dappled canopy or the babble of the passing stream can transport you back to any time in the past one thousand years.

The Allerton Project – a research and educational trust - is not your typical mixed lowland farm, but a demonstration site bequeathed by the late Lord and Lady Allerton on their deaths in 1992 to investigate the beneficial interactions between the natural world and productive agriculture. The site soon came under the auspices of the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust, a relationship which endures to this day.

Although we are an active, modern farm, we also have a team of research scientists on site to measure the impact of different farming techniques on the environment, and for three decades we have been industry leaders in the implementation of habitat creation and biodiversity enhancement in an effort to demonstrate that profitable farming and a thriving environment can exist side by side in our landscape. We have our own visitor centre for organised group visits, and host some 3000 people per year as we seek to demonstrate the good work which British farmers can do, while also offering training courses in environmental management and farming.

We grow a wide range of crops on our arable land, which is heavy and challenging clay; winter and spring wheat, barley, oats and beans, and winter oilseed rape. Our permanent pasture is grazed by sheep, who also take advantage of herbal grass leys which we rotate around our arable land in order to improve weed control and soil health and structure. Some 12% of our land is removed from production altogether and tended for nature – a figure which doesn’t include our woodland, wetland, hedges and ponds, which are all havens for birds, bees and bugs.

Most importantly, I’m joined in my new venture by my ever-faithful canine companions, Ted and Toby, who are learning the ropes of the new farm with the effortless composure of real pros – though I have made sure to give them a stern briefing about the importance of not bothering the ground-nesting birds and other priority species we have on the place (as well as the sheep). And, not that I don’t trust them (though I don’t!), but it’s best that the boys are kept on a lead at all times when we’re out and about – just in case.

A new farm means new field names to learn, and as with most farms, Loddington has a veritable panoply of identifiers – some common and explicable (Church, Railway, Forty-Four Acre fields), some no doubt named for known people, otherwise long-since forgotten (Churchills, Ernie’s Hill, Alan Townsend) and others by turns unique and inexplicable (Paradise, Borrow Hill, King’s Yard.) When first you start, these names are all mystifying, but after only a few weeks soon become familiar, so often are they used to direct the day’s activities. Sent to a field at the north of the farm with the combine harvester, you certainly don’t want to find yourself stuck down a narrow country lane attempting to reach the wrong field to the south.

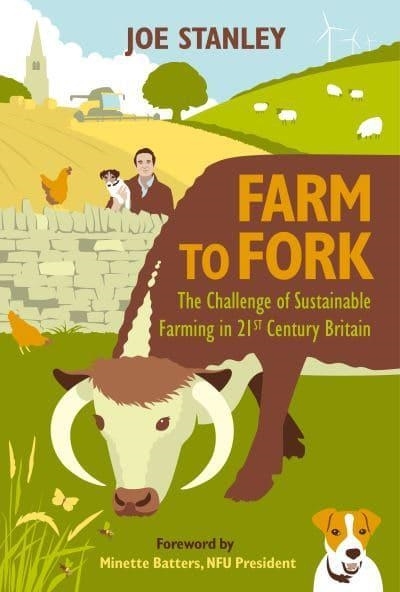

Another exciting piece of news is the forthcoming publication of my first book – Farm to Fork: The Challenge of Sustainable Farming in 21st Century Britain. My intention when writing was to explain to the general reader the realities of modern British farming, much as I hope to do in these pages. To my mind, although there are many excellent titles out there set in our sheep-rich uplands, there wasn’t anything which covered the much broader scope of our lowland mixed farms from which the majority of our food comes and with which we are most passively familiar.

I hope to explain why farmers do what they do, and why, and the path your food takes from farm to fork, while also examining issues such as the impact of Brexit and climate change on British food and farming and what the future holds. It’s been a huge privilege to have been given the opportunity to write on these issues about which I am so passionate, while writing a book has been a dream of mine since I was a child. Needless to say, interspersed through the 300-odd pages are also plentiful tales of Ted and Toby, who even managed to get themselves on the cover. I can’t wait to hold a genuine hardback copy in my hand!

Order your copy from the GWCT here >

As I write, round bales of crisp hay lie waiting to be collected in our fields, the winter barley stands on the cusp of harvest and a new environmental scheme is scheduled to be established for the next five years. A busy few months lie ahead for the farm, and I’m looking forward to bringing you the happenings from this new and interesting place. One thing is unlikely to change, however – our dependence of the kindness of the weather gods. So let us hope for fair skies and a following breeze as harvest 2021 gets underway.