By Mke Swan, GWCT Head of Education

With all the news about new rules for trapping stoats, and changes to general licences for corvid control, it’s easy to forget that there are other predators out there that we need to address, and now is a good time to be on the case. With most of our game nesting, and lots of other wildlife that stands to benefit from our activities, spring is a key time to control common generalists, including the American mink.

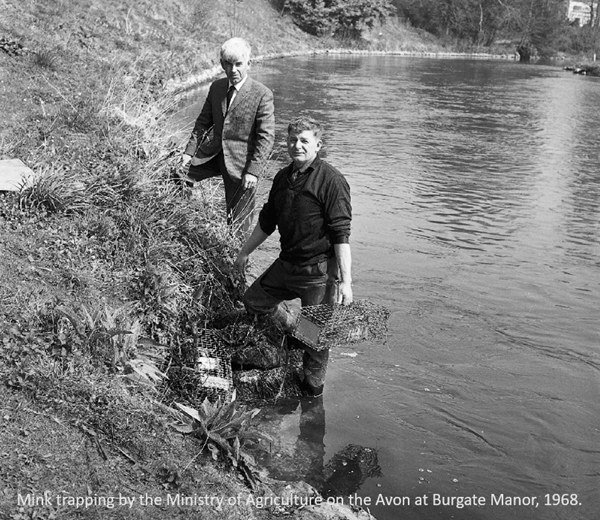

In the late 1960s my father spent several years of his Ministry of Agriculture career working on improving mink control. Indeed, he got so familiar with them that he christened the species “inky stinky”; not a bad name for an inky black predator with a propensity for evacuating its far from sweet smelling scent glands when threatened.

Amusingly, Dad even trapped mink on the banks of the Hampshire Avon, at GWCT headquarters (see photo above taken at GWCT HQ in Fordingbridge in 1968, my father is in the foreground), and it was that introduction that led to him giving talks to gamekeeper courses, and eventually me becoming part of the GWCT team.

That 1960s work led to a much better understanding of how mink operate, developing the conventional trapping techniques that are still widely used today. In the process the MAFF boys refined and improved the mink cage trap. In the fashion of the time, some senior officials even said that if the likes of Fenn and Sawyer could have their traps named after them, father’s name should be on the mink cage. Dad was having none of it, saying; “Some twit somewhere will think it is for trapping swans”.

A Crazy Hunch

Twenty or so years ago, the mink story came full circle, when the GWCT predation research team decided to try to get a better handle on them. Having recently hit on a great way to catch crows and magpies, by using Larsen traps and keying into their territorial instinct, they asked the question “what really matters to mink”?

Could rafts be an answer? Rafts had been used on the tidal waters of East Anglia as a key part of the successful coypu eradication programme, so it seemed worth a try, especially as the coypu traps often caught mink. It was as sure as heck that they were not coming for the carrots used as bait, so perhaps there was something about rafts? It was also the case that floating flotsam piles, had already proved to be good sites for a cage.

A First Experiment

As a first dabble, we gambled with the future career of a summer student, Rhian Leigh, and asked her to see if she could detect mink presence using rafts with a tunnel and a clay tracking pan. Working in the upper Avon catchment, where the 20% of the local river keepers thought that they had mink, our GWCT team did a thorough survey, and found mink signs at 30% of the chosen raft sites. The rafts then detected mink at 55% of sites, showing a huge potential to help with mink control.

The Lower Itchen

Having been impressed by our early results, the Environment Agency found a small pot of money that needed using up before the year end, that enabled us to take the project to the next stage. Using what was christened The GWCT Mink Raft on the river Itchen between Winchester and Southampton, our team were able to remove the mink on 10km of river and associated carriers within a few weeks, keeping it that way for the full summer season.

Further experiments on other catchments showed the same things; rafts are far more effective at detecting mink presence than other methods, and they are also superb trapping sites. If you find footprints on the clay pan, slip in a cage trap, screw it down, and you can expect to catch the mink within a few days, unless it has either moved on, or you have already caught it elsewhere. Just like the Larsen trap, the GWCT mink raft is a highly reliable and target specific – much better than what went before.

Check When You Like

Once a cage is set, you need to check it every day. Failure to do so, risks leaving a live mink in a cage indefinitely and would be a breach of The Animal Welfare Act. This is one of the two key problems with conventional trapping. You need to check cages every day, even when there are no mink to catch. The other is that when there are no mink, you can only catch non-targets. With just its clay tracking pan in place, you can check your raft whenever it is convenient; and only set a trap when there is something to catch.

Rafts will work on pretty much any sort of water; rivers, streams, drains, ditches, ponds and lakes. They do not need to be out in the middle, and there is no need to disguise, other than from interfering people. If your stream is prone to spates, anchor it in a backwater, where it will be likely to get flipped up onto the bank and out of the way of the main torrent when the waters rise. One raft per km of water course seems to be a good rate of distribution, and there is lots of detail on how to use them on the free fact sheet that you can download from the GWCT website.

Humane Despatch

Early in our project, the GWCT team developed the use of a powerful air pistol as an unobtrusive way of dealing with a cage trapped mink. If you choose this method, please follow the advice in the fact sheet to the letter. Using a .177 airgun rather than a .22 may seem counter intuitive, but the small steel pellet is in effect a sharp instrument that penetrates the skull much further. For most of us the much easier method is to use a shotgun from ten or a dozen paces, and I can vouch for the fact that no. 4 steel shot neither destroys the trap, nor ricochets more than lead. That said, safety glasses are an obvious precaution, as well as hearing protection.

Mink control is another one of those many areas where shoot management and mainstream conservation go hand in hand, and all shoots that have water really ought to be running a raft or two. The cost and effort are both small, but the rewards are very real.

Box – Why We Need to Control Mink

When we think mink control, we tend to think water vole conservation, but there are lots of other reasons. Most predators will ‘surplus kill’ given abundant prey, but mink are particularly strong on this, hence the mayhem if one gets amongst your newly released poults in their pen. Similarly, one visit to a nesting gull or tern colony on a little island is all that it takes to destroy the lot. They will also kill nesting ducks and waders, spawning trout, and other fish. The League Against Cruel Sports may be of the view that they should be an honorary native, but most rational people would disagree.

This article first appeared in Shooting Times