Written by Mike Short, Predator Ecologist

Daybreak, on a dank morning in mid-April last year. Peering through my binoculars, I scanned the raised bank of a ditch along the edge of a wet meadow by the River Avon where three pairs of lapwings were nesting. I could see an untagged fox pacing around a clump of rushes where I had set a snare, and hoped it was the vixen whom I’d previously recorded on a trail camera set in the same area.

Donning my GoPro head-camera (a requirement of the Home Office licence that allows us to capture foxes for scientific research), and laden with field-kit, I dashed towards it, staying low so the fox only rumbled me when I was about twenty yards away. I could tell by the state of the capture site that it hadn’t been there long; the fox was feisty, but after it sunk its teeth into the carpet attached to my handling tool, I swiftly grabbed it by the scruff of the neck, and had it under my control.

Offering something for foxes to bite on, like a piece of carpet, helps brings them under control.

She was a non-breeding adult female, still in her thick winter coat which was beginning to shed. She had particularly dark belly fur, and there was no sign of her having suckled cubs. Physically, she appeared in tip-top condition, although she bore an old jaw injury, which had healed well. After fitting her with collar 6644, I snipped the snare cable, carried her away from a cluster of neighbouring snares and let her go. As always, I asked her politely to leave our lapwings alone.

Foxes can behave quite differently when they’re released after tagging. Unsurprisingly, most are eager to get away, but others will loiter and simply glare at you, possibly feeling that the strange new contraption around their neck means you must still have authority over them. Vixen 6644 lay down and eyeballed me. I walked backwards to give her some space, and when I stepped forward again, I fully expected her to leap up and run, and that’s exactly what she did, before jumping the ditch and disappearing into thick cover.

Vixen 6644 was caught, tagged and released on a river meadow where lapwings breed.

Several hours later, I logged into the web-portal which enables us to keep a close eye on the movements of tagged foxes. Most of the time, tags are programmed to record a GPS location every 10 minutes, and field-testing of collars shows fixes to be accurate within 5 metres. Vixen 6644 was shown to be inactive in cover, probably resting. I assumed she belonged to the same family group of fox’s that occupied these river meadows, two of which I had already tagged. But that night, she began an eye-opening journey…

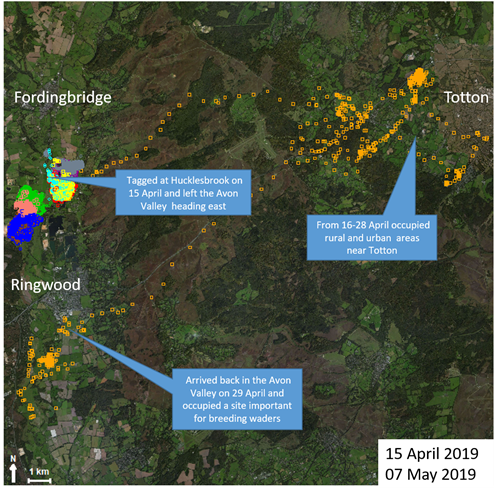

Overnight, 6644 left the river meadows, heading east. Travelling purposefully along the course of a stream and navigating along forestry tracks, her tracking-collar records her venturing about 25km across the New Forest, before she settled in a rural location near Totton, a suburb of Southampton. She mooched around there for several days.

One night she ventured into Totton town; on another she surely diced-with-death, as her tracking data suggests she went foraging along the hard shoulder of the M27, where I envisaged her scavenging roadkill. Perhaps this was her home-turf, and she was caught following a one-off excursion to the Avon Valley? Whatever, she was certainly a long way from those breeding lapwings right now… but not for long.

A week or so later, 6644 was purposefully on the move again, heading south-west. Leaving the village of Ower at around 10pm, she travelled about 20km across the New Forest to the Avon Valley, some of her journey following the A31 road east of Ringwood. By 5:00am she had settled on the edge of a shooting estate, home of the most consistently productive wader breeding area in the valley.

The estate employs a first-class gamekeeper who invests a great deal of effort in culling foxes and other generalist predators during the nesting season, which helps lapwing and redshank to thrive here. He has often asked me, “Where on earth do all these foxes keep coming from?” Well, this one came from near Southampton.

The coloured symbols show the individual locations of tagged foxes. The orange squares reveal the movements of vixen 6644 during the period she was tracked. She was tagged on river meadows near Hucklesbrook just south of Fordingbridge. Shortly after release, she travelled eastwards towards Totton, before eventually returning to the Avon Valley again.

Contains Bing imagery © Microsoft Corporation 2019.

That she was so close to a LIFE Waders for Real project hotspot site, left some of our team full of consternation, which was understandable. Perhaps I can hear some of you saying, “I hope you immediately told the gamekeeper exactly where she was?” Well, no, we did not, because as scientists our aim here is to try and unravel the lives of foxes around breeding waders, using expensive technology. This certainly wasn’t the time to play Judas. We had too much to learn from vixen 6644, and so did the gamekeeper.

She occupied our Kingston and Watton’s Ford hotspot sites for ten days and we now have a unique insight into how an adult fox travelled and foraged around meadows important for waders, on a site where foxes are routinely culled.

We know that 6644 travelled along a dirt track that separated two electric-fenced areas used to protect breeding lapwing, and that she unwittingly passed a redshank nest on this same track, from which chicks later fledged. She was eventually detected by a trail camera belonging to the gamekeeper, but she was never detected by 20 other cameras maintained by the bird monitoring team, in the same area, through the same period.

Trail cameras are popular among biologists and gamekeepers alike, and foxes are one of the most commonly recorded species. However, ‘no detections’ doesn’t necessarily mean ‘no foxes’. This example shows how a fox can remain undetected for quite a time despite a good density of cameras.

This image of vixen 6644 was recorded on a trail camera maintained by the estate gamekeeper.

Following her detection on his camera, the gamekeeper made use of a high-seat close by and within a few days of waiting for her around sunset, 6644’s days were numbered. He was apologetic for having killed her, but he had a job to do, and it was a fitting end to a fascinating story. That this fox was able to live around breeding waders for ten days before she was detected and removed is thought provoking.

For wildlife managers, her story illustrates how tricky it can be to detect foxes, from how far away immigrant foxes may originate, and why continuous culling might be required to maintain low fox density. It also reveals the scale at which we should attempt to understand how the availability of resources in the wider landscape, determine fox population pressure in areas important for breeding waders.

Whilst GPS-tracking of foxes in the Avon Valley has documented the strict territoriality of most foxes resident around river meadow habitats, it has also revealed the surprising mobility of others. We don’t know where 6644 originated from, but she showed how easy it is for a fox to travel 20 km in one night.

Southampton and Poole/Bournemouth are two of the largest conurbations on the south-coast and may be important source areas of foxes that migrate into the valley, either temporarily or until they are culled by gamekeepers, as we saw with vixen 6644. But it is also feasible that foxes disperse here from other rural areas where abundant food resources enable them to breed well.

We had no plans to tag foxes again this year, but our research on foxes in the Avon Valley is far from over. We still have an enormous amount of work to do, by way of mapping and making sense of the location data (circa. 170,000 GPS fixes) for 37 foxes, which requires the application of laborious and complex analytical skills.

Aside from writing new guidance documents for site managers, we aim to publish several scientific papers to help inform future policy decisions on predator management for wading bird conservation to help breeding lapwing, redshank and curlew populations to recover.

Another legacy of our tagging work is a new collaboration between GWCT and Bournemouth University, with a PhD project intended to commence in September 2020. The aim of this is to determine how the regional dispersion of resources and consequent population dynamics of foxes affect the predation pressure experienced locally by wading birds that breed in the Avon Valley.

The wretched COVID-19 has temporarily thrown a spanner in the works, and is disrupting our progress, but we thank those who continue to support the GWCT’s fox research during these tough times.

Find out how you can support this important work so that the people managing our countryside have the best chance of making a difference >