Reintroductions of native species is becoming more common, but how welcome are they asks Mike Swan

They are coming at us from all directions; reintroduction of native species has never been more fashionable and its going on apace. The capercaillie was probably the only one in the 19th century, but over the last 30 years there have been lots more; wild boar, white tailed eagles, and beavers, all of which were completely gone from the UK. There are also red kites, otters and pine martens, which have been or are being restored from relict population, and a whole host of other more local reintroductions too, like grey partridges and water voles.

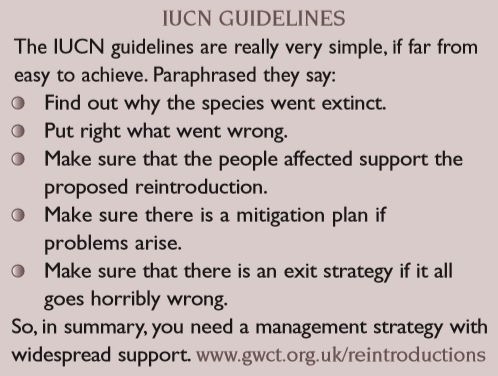

So, how does the GWCT steer a consistent policy line over all of this? The answer, which was proposed by Steve Tapper 25 years ago, and which remains to this day, is that reintroductions are welcome provided that they meet the guidelines set out by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Casestudies

Beaver

There are now several beaver populations in the UK, notably the Tayside area, the river Otter in Devon, and the Knapdale Peninsula in western Scotland. The latter were released as a Government approved trial, but both other populations are the result of escapes or illegal releases.

Beavers are hailed by their protagonists as ‘nature’s water engineers’, with a list of attributes like trapping silt, minimising flood risk by impounding water and creating pools for fish and other wildlife. However, there are problems too, like creating dams in the wrong places, undermining flood defences where they dig into banks, felling important trees, eating farm crops and impounding streams to the detriment of migratory fish.

Currently, those whose interests are damaged by beavers have the right to control them, but there are moves afoot to restrict this, which will surely lead to conflict. Speaking to farmers from Tayside who are living with beavers, I got the overall impression that while they would rather there were no beavers, they could live with the current situation, but further restriction on their ability to control would be unacceptable.

Against this background, it is important to recognise that beavers are flourishing in this rich lowland environment, despite control; spreading into new areas all the time. In contrast, in the harsher world of Knapdale, the population is not doing well and there is talk of releasing a few more to help the population. Could it be that Knapdale is just not suitable for beavers?

Following IUCN guidelines, the reason for the lack of success needs to be investigated and corrected, before more beavers are released. It is also clear that beavers prefer rich lowland environments where the potential for damage is greatest, rather than the harder going upland situations where their impoundments could just help to store water and reduce flooding lower down.

Pine Martens

The pine marten is a relatively large mustelid; a bit bigger than a ferret, with longer legs, a bushy tail and a penchant for climbing trees. No one quite knows where they remained in the UK, but their main refuge was north western Scotland. There were reports of odd individuals surviving quite widely, notably in Snowdonia and northern England.

In the last few years, the Vincent Wildlife Trust (VWT) have been reintroducing them to west Wales, and unlike most reintroductions, this has been fully legal, with good regard to IUCN guidelines. However, even here the story on mitigation in the event of problems has been weak. VWT have said that any of their pine martens that cause a problem can be easily trapped since they have been fitted with radio transmitters. This fails to recognise that ultimate success means a freeliving breeding population without radios. Since the species is also protected under schedules 5 and 6 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981), this means that anyone with issues in the future will need to apply for a licence to intervene.

Most gamekeepers will quietly be quite worried by this. A large mustelid that can climb trees and hunt roosting pheasants is not likely to be popular. That said, there is good reason to believe that pine martens will have a significant effect on grey squirrels, perhaps even allowing the native reds to recolonise in some areas.

Grey Partridges

Surely no one could argue with the desire to reintroduce grey partridges where they have died out. However, if we are to cry foul when others fail over IUCN guidelines over their reintroductions, then we must surely abide by them with our treasured greys. This means following GWCT science and making sure that we have addressed the environmental issues that have made them disappear. It also means using the best possible stock, and not just letting out some naïve brooder-reared poults into an unsuitable environment, where they are bound to fail.

WHAT IS YOUR VIEW? Should we be reintroducing native species? Email us at editor@gwct.org.uk

(Clockwise from top) Wild boar, grey partridges and beavers are all species that have been reintroduced.