It all began as a bet, and in a way it changed my life.

It was 1990 and I was walking with a gamekeeper, Russell Evans, on a shoot in Cheshire. I found him such a rich source of knowledge about birds and nature in general and I always enjoyed talking to him. On that particular day a woodcock had been shot and I asked to see it, as I had not seen one up close before.

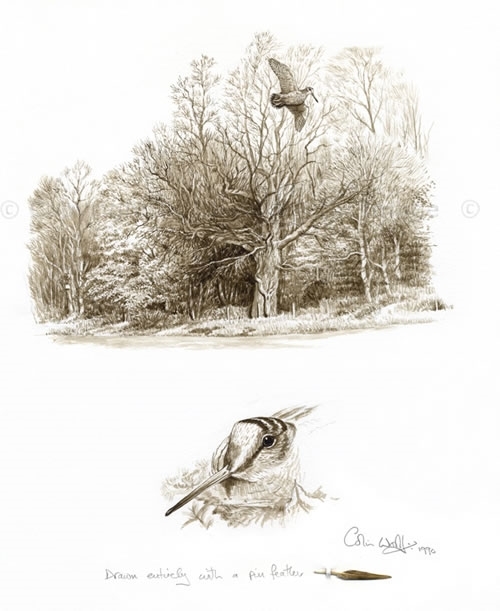

He pulled the pin-feather out and showed it to me, asking if I knew that these feathers were once used for painting with, and were highly prized by artists. I was astonished. Why would anyone paint with a feather? Russell gave it to me with the instruction to go away and try.

I am pleased to say that the first painting is still on Russell's wall. Since then, I have been asked to paint many pictures for guns who have shot their first woodcock. I also use this technique at all the shows where I demonstrate. It is so unusual, and people are fascinated to hear about it.

Interestingly, I was told many times by members of the public that pin-feathers were often used for painting, and I was occasionally approached by specialist magazines, for example art restoration journals, seeking more information regarding their use, but it was a long time before I had any proof that pin-feathers were actually used in art.

I was therefore extremely excited when I was shown an artist's painting box dating from the Victorian era. The original owner, Lady Letitia Louisa Kerr, was a well-respected miniaturist and I was fascinated to discover within it a small cardboard container with some woodcock feathers inside.

On the lid, in faded copperplate handwriting, were the words “Woodcock’s feathers for miniature painting”. At last, I had some evidence that pin-feathers were indeed used for art, and one even had some traces of paint on its tip. I was extremely fortunate to be given a couple of these feathers, which must be between 150 and 185 years old, and I could not resist trying them out. One of the results, a painting which I called ‘Old Acquaintance’, is shown here.

In terms of anatomy, the pin-feather sits on top of the first primary on the leading edge of a bird’s wing. The woodcock is not unique in having a pin-feather, and in fact I have an interesting collection of specimens from about 50 different bird species. However, when you inspect them, it is easy to see why woodcock feathers were preferred for painting.

My love-hate relationship with pin-feathers stems from their unpredictable qualities, which range between frustrating and impossible. Speaking personally, although I relish the challenge of painting with pin-feathers, I will never prefer them to a brush. When wetted, modern watercolour brushes produce a lovely point, no matter which way you turn the brush or how you present it to the paper. Using a pin-feather requires a specific kind of action and a delicacy of touch that is very wearing for the artist.

To start off with, every feather has its unique properties but invariably only one of the two edges is useable. The useable side will only be found after trial and error. This is not a relaxing way to paint. As an artist, you need to have faith that the stroke you are about to make with the brush or feather will be predictable; the problem with using a feather is that it is not in any way predictable.

There is also the issue of a very short life-span. The tip of a pin-feather wears down quickly and the barbs fall off after only a few hours of use. Having started off being stubbornly waterproof and refusing to transfer paint to paper, the feather often ends up becoming waterlogged, which necessitates a drying-out period between uses. By the time I have completed a painting of reasonable size - slightly less than A4 is about the maximum - the feather is almost completely worn out and the tip will be ragged, quite often worn down to the central spine.

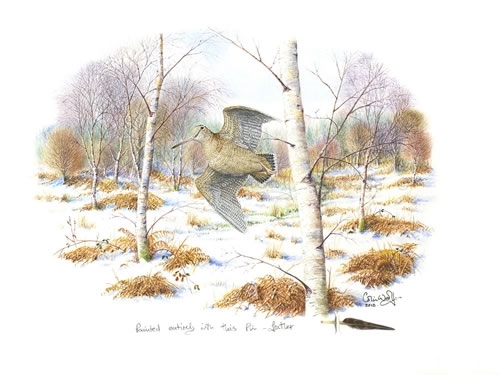

Because of all these issues I always paint the bird and the more detailed areas first, because afterwards I can paint the background trees with the worn tip. Washes for the sky are achieved by laying the feather down and using a wet-in-wet technique, which is best done before the detail is added. Somehow, I have always managed to complete each painting using only one feather for the whole picture. The feather is carefully inserted into the paper before framing, and below it in pencil I will write the words ‘Painted entirely with this pin-feather’ - a phrase which has become a hallmark of my pin-feather work.

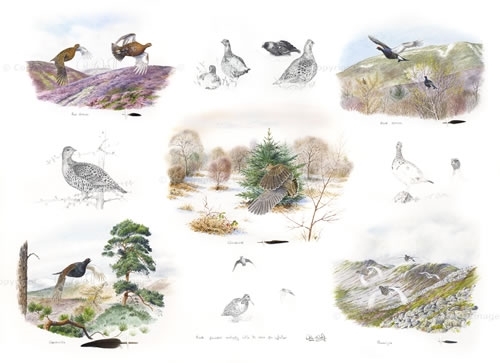

After about twenty years of battling with woodcock pin-feathers, I started to wonder what the feathers of other species were like to paint with. In 2012 I decided to set myself a challenge: I wanted to create a large composite painting that included five different species, each painted with its own pin-feather. It was natural that the central painting should be a woodcock, while around it I would place red grouse, black grouse, capercaillie and ptarmigan. Since it was an Olympic year, I called this my ‘Olympic challenge’.

Having made that decision, I had to find the feathers. It took me a long time to obtain pin-feathers from capercaillie and black grouse, but thanks to Alistair Mackie, a specialist breeder, I obtained some feathers from casualties. The scarcity of some of the feathers presented a worry. I have a large number of woodcock feathers to choose from, but for some of the more unusual species I only had two. Interestingly, in practice the huge capercaillie feather worked incredibly well, while the small but nicely-pointed ptarmigan was by far the most difficult to use.

With the success of this painting behind me, I began to think of more species and another Olympic challenge was born. This time the birds included pheasant, grey partridge, teal and snipe. I had used snipe’s pin-feathers in the past and knew how difficult they were to use; however, the grey partridge’s feather was so soft that it takes the prize for being the worst to paint with.

At shows around the country I am sometimes given pin-feathers by members of the public. One day a man handed me a packet of pin-feathers from pink-footed geese. These are nearly two inches long, and at the time I just laughed and dismissed the idea of painting with them. But the idea still nagged at the back of my mind. What if I could do a goose-themed painting?

I knew that if I was to complete a third Olympic challenge to match the existing two, I would need feathers from four species, but only three species of goose can be shot in most of Britain. Ireland has different laws, so I was hopeful of eventually obtaining all four species. Four years later, a small envelope arrived in the post, and I was ready to begin.

I like to think of painting with goose-feathers as being akin to painting with a piece of tissue attached to a grass stem. Added to this, the feathers are so flexible that they have a sudden spring when you apply the paint to the paper, causing the tip to flick upwards. The placing of each stroke became a nerve-racking exercise. After much perseverance and concentration, I completed the painting and ultimately my trio of Olympic challenges. Of them all, I am perhaps proudest of this last one, just because of the effort involved.

Over the years, other interesting projects have cropped up. Some examples include an American woodcock, a golden plover, a curlew, a woodcock ‘right-and-left’ (using pin-feathers from the same bird). Each one began with an initial response along the lines of ‘that’s impossible’.

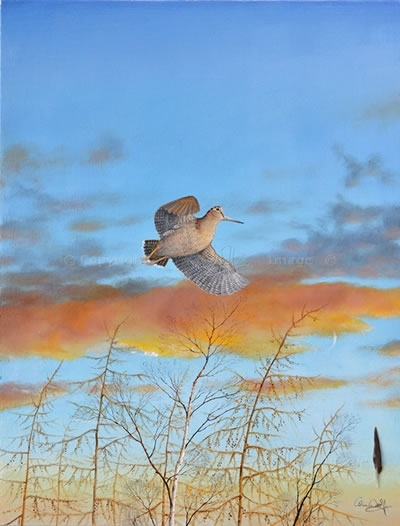

And the latest challenge? Another change, not of subject this time, but of medium. I started life as an oil painter, but eventually settled on watercolours as a wildlife artist. So it seems quite fitting that my last pin-feather challenge should be in oils. How does a woodcock pin-feather behave with oil paints? Strangely, the feather doesn’t wear out so quickly, presumably because the oil acts as a lubricant.

However, the application of paint seems to elude and evade the most gentle of strokes. It was a whole new experience, just when I thought I had exhausted them all.

It remains to be seen whether any new challenges present themselves. I have learned not to say ‘never’. If I had given that first feather back to Russell Evans all those years ago, like any sensible person, none of these challenges would have arisen. However, I like to think that if you have one of my pin-feather paintings on your wall, no matter what the species, you possess a little piece of artistic tradition that I am happy to be keeping alive.

More examples of my pin-feather work can be found on my website >

If you would like to own one of these uniquely beautiful works of art, I would be happy to hear from you. I’m able to create a particular 'theme' within the painting, e.g. winter, autumn, sunset, or birch woodland. NB: I’m not looking for more impossible challenges (at the moment!)

You can read more about the pin-feather painting here >

You can read my latest book on this subject here >

You can view my website here >

Promote your business with the GWCT

A GWCT Trade Membership entitles you to a FREE guest blog spot which will be promoted directly to over 30,000 GWCT members and non-members alike.

GWCT Trade Membership benefits >