By Alastair Leake, GWCT Director of Policy

By Alastair Leake, GWCT Director of Policy

As the UK prepares to leave the EU, and thus the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), we will need a new British agricultural policy. George Eustice MP (Minister of State at Defra) outlined key priorities at the Standing Conference on Countryside Sports and Management last week.

- How to best achieve market stability (and continuity)

- Environmental benefits (‘ecosystem services’ in policy speak)

- Flexibility of administration (to enable constant evolution)

- New technology (and how that can be encouraged)

- Introducing fairness to the supply chain (spreading the risk)

- Animal welfare (to enable our high standards to be sold to the world)

As NFU President Meurig Raymond explained at the same conference, reforming the annual £3.2bn CAP will be challenging. Meurig also announced that the new NFU vision is “countryside that works for all”.

Why farming policy is central to conservation

Agricultural reform matters to our wildlife because most of it does not live on nature reserves – it lives on our farmland. On our small, busy island, where agricultural land makes up about three quarters of the total land use, it will always be this way. Farmers are central to the success of our national conservation policy.

Many naturalists and conservationists are more inclined to see farmers as villains. It is unfortunate that the 2016 State of Nature report, written by 50 conservation groups (not including the GWCT), fell into this trap. Wildlife declines over the last 50 years were simplistically blamed on farmers.

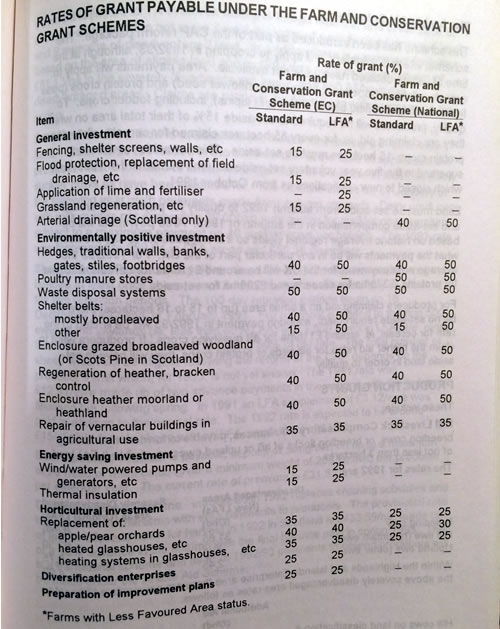

Memories are wonderfully short. As recently as 1975, just after the UK joined the EEC, the UK agricultural policy white paper Food from Our Own Resources was published. Producing low-cost food production was for the public good. The 1992 Farm Management Handbook explains (below) that 50% grants were available to “enclose heather moorland or heathland” – something unimaginable now.

Farming practices have changed. For example, the basic agri-environment scheme (Entry Level Stewardship), has been implemented and some 70% of farms in this country have adopted it.

What does the GWCT think should happen next?

Leaving the EU is an extraordinary opportunity to develop a new British agricultural policy, but we don’t feel we must develop a new countryside policy from scratch because we already have two robust British reviews:

1) The Curry report

The first is Food & Farming, chaired by Sir Don Curry in 2002. It was commissioned by the government immediately after the foot-and-mouth disease outbreak. Its remit was visionary: “advise the government on how we can create a sustainable, competitive and diverse farming and food sector which contributes to a thriving and sustainable rural economy”.

2) The Lawton report

The second is Making Space for Nature, chaired by Sir John Lawton in 2010. It was commissioned by the government to review England’s approach to wildlife conservation. Many will remember that it summarised the essence of what needed to be done in four words: “more, bigger, better and joined”.

What next

Some may be aware of the initiatives that were actioned from these two substantial British documents: support for the Red Tractor food label, the evolution of agri-environment schemes and, more recently, Nature Improvement Areas (NIAs). Those who have read them tend to remember the bits they either did or did not like.

We feel what needs to happen next is to go back and review the ideas that were not actioned – for both farming and wildlife. The farming policy issues are of particular interest to us – the GWCT has two demonstration farms, one in Leicestershire and one in Aberdeenshire. Some examples include:

Conservation Covenants

The Law Commission recently published its review of Conservation Covenants and the GWCT strongly supports this type of voluntary approach to conservation. Our experience shows that willing conservationists working in partnership with conservation organisations make better custodians than those ruled by the enforcement of compulsory schemes. The latter run the risk of the landowner feeling a degree of resentment to imposed management plans. More on this from the GWCT here.

Biodiversity offsetting

This is an idea to compensate for habitats and species lost to development in one area, with the creation, enhancement or restoration of habitat(s) in another. Under this system, any negative impacts on the natural environment would then be compensated for, or ‘offset’, by developers.

A simple idea but it sets fear in the minds of some. If you read Lawton’s recommendation (p86-88), you will see just how much he thought this through. He knew some may label this a ‘licence to trash’ and he was keen to avoid that.

The GWCT is actively involved in a great crested newt conservation initiative. They are currently located on an island site surrounded by development, which, all agree, is doomed. It makes complete sense to us that since steps one (prevent loss) and two (mitigate against loss) have failed, we must move to step three (offset loss). More on this in the future.

Commercial routes or market-led initiatives

We see this as another big area. Lawton identified the potential for new markets and payments for environmental benefits. This is, in our experience, happening already. Organisations with robust environmental positions such as Kellogg’s are doing just this. It may be that education, training, R&D or paying a premium for a product to the supplier are all valid. It should be encouraged further, but we recognise some may need careful implementation. The logic of paying a supplier a premium for a product or crop because it has clear environmental benefits is well understood – but farmers are not foolish businessmen, and payment by the unit may encourage higher levels of production and inadvertently reduce the desired environmental outcome.

Direct payment for environmental benefits (or ‘ecosystem services’ and ‘natural capital’)

There has always been a recognition that the state will need to intervene for the public good where there is no market. Both ecosystem services and natural capital are now government policy. The GWCT sees both as important. Whilst the detail is established, it is also important to clarify the scale of funding and how it will be administered.

What is likely to happen to future farm funding?

The treasury has underwritten future funding up to 2020 but what replaces it is not clear. The future options are wide:

- The existing Basic Payment Scheme will probably go. Transitional arrangements are not clear.

- Direct farm payments replaced with environmental payments.

- Upland farming support is more likely to remain.

- Reduced payments to larger farms? (The SoS said no to this.)

Future environmental policy

Once all legislation has been transferred into UK law, it is expected that the next ten years or so will be spent revisiting what we want to change. The GWCT will seek to make it easier to manage wildlife (e.g. ratchet species protection up/down as required and ensuring we are measuring conservation success levels). Species protection, alone, has not been enough to reverse the biodiversity losses in this country. We feel this is a golden opportunity to achieve a fundamental shift towards managing our wildlife – to achieve significantly better outcomes.

Help us seize the biggest opportunity for conservation in a generation

As a nation, we must remember that the real enemy of conservation is often uncertainty not change. Change in policy can help our countryside to thrive.

Any donation you can give will get our research into the hands of politicians and the public.

- £25 could help us prepare a factsheet on the burning issues facing the British countryside

- £100 could help us to use this literature to brief a politician, ensuring they are aware of the opportunity for conservation policy

- £250 helps us to raise awareness for practical, evidence-based conservation policy with a wider audience – be it in the press, on television, on the radio or online

This is a once in a generation opportunity to redefine our approach to conservation. We know what must be done to tackle the challenges facing our game and wildlife and with improved conservation measures and a wider understanding of the issues facing us, the countryside can thrive. You can be a part of it.