Why some trout migrate out to sea and why some stay in their natal river has fascinated fishermen, but now a new study is providing some answers. Jill Goodwin explains.

Why some trout migrate out to sea and why some stay in their natal river has fascinated fishermen, but now a new study is providing some answers. Jill Goodwin explains.

Brown trout and sea trout are the same species (Salmo trutta L.). Some individuals (sea trout) migrate to sea before returning to spawn in the stream where they were born. To cope with the marine environment, they undergo changes in physiology and colour, and, as food is more plentiful in the sea, they grow to a larger size than if they had stayed in the river.

Other individuals (brown trout) complete their whole life-cycle in freshwater and grow up to become the spotted beauty that we know and love. This difference has fascinated scientists and anglers alike, raising questions such as ‘What advantages do individuals gain by taking on the costs and risks of migration?’, ‘How are the two forms related?’ and ‘How important are sea trout for recruitment in trout populations?’

Recent work undertaken by a team from Exeter University, the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Queen Mary University of London, and the GWCT has provided answers to some of these questions. The team studied a trout population in the River Frome, a chalkstream catchment in Dorset, at a site used for breeding by both brown and sea trout.

In this study, recently published in the journal Freshwater Biology, the team used a novel combination of stable isotope analysis and microsatellite genotyping to unambiguously identify the maternal origins of 78% of the juvenile fish. The genetics also allowed the team to establish the paternal origins of a large proportion of juvenile fish. The team then used these data to determine the relative contributions of brown or sea trout to the next generation of fish, and to establish if there was any advantage to the offspring associated with their mother’s life history.

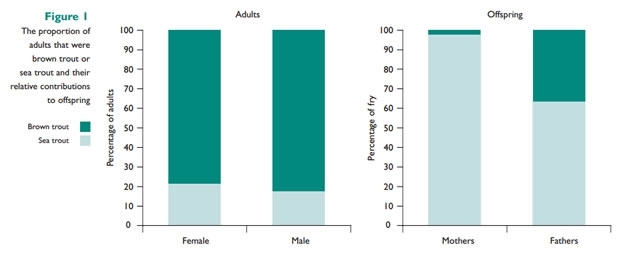

The results were fascinating: although only one fifth of the adults (both male and female) were sea trout, they were mothers to 97% of the offspring in this population (see Figure 1). Surprisingly, just six female sea trout contributed 76% of the newly-born fry, with the number of offspring related to the size of the mother; it was also clear that individual females were breeding with multiple males. Conversely, despite their larger numbers, female brown trout contributed just 3% of offspring.

Male brown trout fared somewhat better, managing to sire 37% of the fry. Male sea trout also fertilised a disproportionate number of eggs (20% of individuals were father to 63% of fry), though size of males was not related to number of offspring.

As well as the adults gaining a reproductive advantage by going to sea, fry also benefited directly from their mother’s choice. Offspring of sea trout mothers emerged on average earlier, and at a larger size than offspring of brown trout females.

Although this study focused on just one river from a chalkstream catchment, it demonstrated that sea trout can be extremely important for recruitment in trout populations.

Please support our Salmon Appeal

We're currently working on finding out why Atlantic salmon numbers have dropped by as much as 70% in some areas. Please give what you can afford so that our scientists can continue their vital work.