Key findings

- Calcein marks remained detectable in all marked fish for 12 months.

- After 19 months, a third of fish still retained an identifiable mark.

- Fish growth not time causes the mark to disappear.

- Marked fish were no more vulnerable to predation by trout than unmarked ones.

- The calcein technique provides a reliable, unbiased method for marking large numbers of small fish.

Marking fish is essential in fisheries research and management. However, marking juvenile fish is difficult because they are small and have to be marked in large numbers. From a range of techniques, bathing in a fluid called calcein seems to offer a good way to mark large numbers of small fish. Calcein is a fluorochrome, which binds with calcium and fluoresces. The compound has been used in quantifying calcium content of stone, for tracing blood flows within the eye and for examining bone growth in animals. Its application to fish using a salt bath before calcein immersion, produces a mark that is detectable without having to sacrifice the fish.

Jerre Mohler of the Northeast Fishery Center, Lamar, Pennsylvania, USA has developed the method on Atlantic salmon and has found no adverse effects. When we first tried the treatment on brown trout fry we were unable to detect the mark despite trying various types of illumination.

In 2005, we visited Jerre Mohler’s laboratory to see how he detected the marks. His salmon had apple-green fluorescent marks when looked at using his prototype viewing device. So, we tried the technique out again on brown trout, with no mortality and 100% marking rate over 24 hours. When we tried Jerre’s viewer on our original fish we discovered that they had been marked perfectly. We decided to develop this technique for brown trout by checking for effects on mortality, mark retention and predation by adult brown trout.

We conducted these studies at Watergates Fish Farm in Dorset during 2003 and 2004. We marked some groups of fish and left others unmarked. We then checked them for mark retention (using Jerre’s device) several times in the first month and then every one to two months for a year and a half.

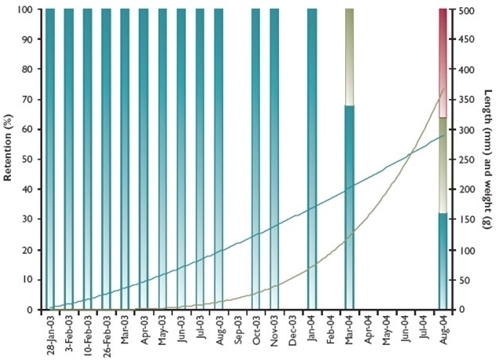

We found that after 12 months, all marked fish were still identifiable as marked. At 19 months, 32% of fish still had an identifiable calcein mark. Over the last seven months of the trial, the marked fish had an average weight increase of about seven-fold to 430g (about 1lb) and length two-fold to 310mm (about 12”) (see Figure 1). We found no difference in survival, length and weight over 19 months between marked fish and fish left unmarked as a control. Jerre finds that salmon of a similar age (17 months) retain all their marks, but they are still small at this age being only 232mm long and 126g in weight. This suggests that it is growth that causes the mark to disappear, not time.

Figure 1: Length, weight and calcein retention in brown trout fry

To see if marked fry were more vulnerable to predation than unmarked ones, we set up six small raceways, included some natural river habitat, and introduced two adult brown trout of about a pound in weight as predators. We then placed marked and unmarked fry into each raceway. After three days we removed the fry and counted what was left.

We could find no difference in the proportions of marked and unmarked fry that had been eaten, which suggests that calcein marking provides a reliable and unbiased method of assessing survival of trout fry in the wild. We intend to use this marking method in our research on fry stocking.